|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

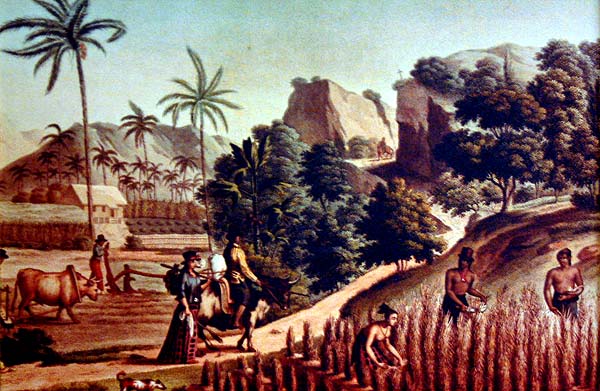

"Cultivation practices have really changed from the traditional to modern methods," Rufo explains, "and I don’t know whether it’s gotten better or worse. Traditional method is the slash-and-burn type of agriculture, that is what is practiced in most indigenous cultures. Funny thing is that when Westerners come in, they say that this practice is wrong. Because they base that on their concept, not on what has been observed and then practiced by the indigenous person. "Even now, we’re finding out that burning out an area does some good, even in forest areas. You do burns, you create an open spot to provide for the species diversity. Fire itself is a natural phenomenon. And with burning, the ash fertilizes the land. So you go slash and burn, then plant there, in small plots."

|

||

|

|

||

|

"You plant normally for three cycles, three years. The Chamorros observed that the fertility of the land is good for that long. When you first clear, you burn it and plant, and it's good for three years. And after three years, then they say 'konsumalo,' meaning it has lost fertility. Time to move to another area. Then it lies fallow and regenerates. That’s the Chamorro agricultural practice. "We have seasonal plants, like the yam. Usually that’s food that’s available right at the tail end of the rainy season. And that’s cultivated. There are different taros, which are also cultivated depending on the season. You have taro that is planted to be harvested during the rainy season, and then taro that is harvested during the dry season."

|

|

|

|

"Corn, which was introduced by the Spanish, was also planted, but corn is a plant that the Chamorros observed to extract the nutrients from the land quicker than other plants. So it was planted judiciously. The other thing that’s seasonal is tapioca. Maize or corn was introduced from the new world, then you have tapioca which is from Africa. "Now you want to grow everything fast. Agriculture is no longer subsistence, it is commercial. A lot of people now grow and plant things commercially, so you want to be able to grow it and let it reach maturity in the shortest time possible, to get your returns on your investment."

|

|

|

|

|

“When Magellan came, he got rice,” Rufo points out. “And the Chamorros planted two types of rice: the wetland variety, and the dry-land rice. But after the Spanish came, that cultivation dried up, because the Spanish ate corn. At least, that’s what they brought over here. So the traditional rice-growing dried up. I think there are only one or two persons planting rice nowadays. And that’s dry-land varieties, you don’t have to create your rice ponds, Fama‘åyan. “You know, in Inarajan the name of that flood plain is Fama‘åyan, ‘the place where you plant rice.’ That’s what the Chamorro name translates to in English. "

|

||

|

|

||

| “Oh yes, we had the rice field,” Tan Floren remembers, “now it’s mostly houses there, but before, on this side and on this other side at the end of the village, all this was rice field, you know. And behind the new In and Out store, that was the rice field. Always in the morning, at like four o’clock, we were there, hunting that rice. "We used carabao to plow with, that’s the only way, because we didn’t have that machine, so the carabao had to pull that plow. It makes it soft, so all we do is just to plant that rice. They put a line, so all you have to do is just plant it in on the mark, line by line." "And then when it’s time to harvest it, so many steps. The people would build something using bamboo. So when the rice is already dried, the people will put it up, and beat it so the rice falls down. Then they put that rice in a big lusong, and we get this stick, people pound it, and then the rice is ready to cook. It’s hard, but the Chamorro enjoy working on it."

|

|

|

|

“Everywhere, the coconut tree—you don’t have to plant, they just grow. When we visited my property a couple years ago, you could hardly walk! No one is coming to pick them up. "Before, we usually went with my sister, and then we’d make coconut milk and sell it. We made money out of it, but not any more. It’s too far, and we’re getting old, we cannot go that far, or carry coconuts that far. So there's a lot of coconuts here; look at all the coconut around. No one is making coconut oil. It’s kind of hard, you know.”

|

“Breadfruit, orange tree, lemmai tree (seedless breadfruit)—there’s all kinds of fruits, like the guava, tangerine, the åtes (sweetsop, or custard apple), laguanå (soursop). The Chamorro had all these kinds of fresh fruits. “Some people planted sweet potatoes. In those days, you could see sweet potato plants around, because they don’t take long to be ready to eat. I think they take about three months. “The taro in the swamp, that’s year-round. The small leaf, that is the good one. The big one is not in the water, it’s in the dry ground. The more you pile a lot of dirt, the more taro you get. The 'Honolulu taro' is white, but the regular one, that purple one, that is good, too. “And then we get a feast. We’re lucky, eh? Just go out and get your net, and go fishing."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inarajan contributes significantly to food production on Guam as a whole. The reason for that is the river bottoms, we are told. Because of the land around these many streams, Inarajan has better soil. "I come from a farming background, and a farming family," Jeff says "Most of the land areas that we have are all in the low-lying areas and those are right next to the river, where there’s a water source. And I know in my family that has been the primary area. Even in our main family land, there’s a major river running right through the center of it, and that’s where the bulk of ranch or family activities are taking place, especially in the harvest of copra."

|

||

|

|

||

"There’s Dåndan, in the Malojloj area," says John. "Malojloj has traditionally been a dry-season farming area, because the soils are too wet in the rainy season. You can’t plow when it’s wet, you damage the soil structure. They grow watermelons and some cantaloupes, and other types of things. "There’s farming closer to the road; there’s mixed farming, and there’s farming down near behind the village, in the bottom lands of the Inarajan River. It’s traditionally been a producing area." "Malojloj, behind the houses," Jeff adds, "there are small patches of farms that are there, and you can see because the lots are vacant and they have everything from cucumbers to bell peppers to beans."

|

|

|

A highland field, also fallow.

|

"The uplands have several problems," Jeff continues. "The soil is acid and it’s very nutrient poor. It’s dry in the dry season and it’s windy so they all combine to make a rather difficult situation. "Sometimes if you look at the watermelon, the vines of the watermelon, you know where the wind is going because the vines would be all gathering in that one direction and then when the wind moves the following day, everything goes out again so, it’s not a normal spread of a watermelon in their vines. It’s usually one direction so all the vines are all going either east or west or north or south."

|

|

|

|

|

''Inarajan is producing 90% of the aquaculture products on the island," Jeff states. "That started around 1969 and the early 1970s. My brother started the first research on aquaculture, and then private investments started coming in during the 1970s. One of the first operations was in Inarajan, by Bear Rock area. It was eel farming for the Japanese market. They used to export eels. Bear Rock was the primary production area for the eels, and there are still ponds down there. "For a very short period of time, Guam—Inarajan—was the third largest eel producer in the world. They harvested late at night, got the shipment up to the airport, got it on that plane by midnight or 10:00 pm or so, and it would arrive in Japan before the morning market began. They shipped the eels live, because they have to be fresh. But then Taiwan came in with a lot better price, affecting the market."

|

||

|

|

||

|

"That market went down," John says, "so aquaculture then aimed at the local market, and largely it has been tilapia, catfish, carp and milk fish. But now the market for most of the fish has been the non-Chamorro population, the Asian population. Chamorros are now starting to buy a lot more tilapia, and they found those can go on the barbecue really well. It’s becoming more popular, so production is actually a little short right now. "They’ve expanded into the newest product going, which is shrimp, salt water shrimp. It largely was Chinese-run for a long time, but some of the Chinese have retired and the leases have gone back to the Chamorro families in Inarajan, who are starting to run the farms a little more." "Aquaculture is still there at Bear Rock," Jeff adds, "but that is just one of five areas. We have 100 acres of fish farms in Inarajan and they go the full length of the coast in the village. Only one farm on the north side of the Talofofo River is outside of Inarajan itself. They’re located right by the rivers, at the river mouth. There they can either get fresh or salt water. So they have a variety." , |

|

|

|

“Guam never had a cash crop until the very end of Spanish times,” Larry points out. “There was copra production, but even then, in Spanish times, a lot of that was controlled by Japanese and Germans. They were selling copra here to the Americans, to Germans, and to Japanese. But before that, there was no real cash crop. The Spanish did force Chamorros to harvest capers for the galleon trade, but that was never a significant cash crop. "The Spanish governors had plans—they'd bring in farmers, farm animals, and farming equipment from the Philippines. Governor De la Corte even suggested the amalgam of immigrant Chinese men and Carolinian women to create industrious farmers for the Mariana Islands. Many claim that Guam was an important stop on the galleon route, but that's not true. They had to have a law to force the galleon captains to stop here. It was a relatively short trip from Acapulco to the Philippines, and because of the trade winds, it was an easy trip. Going back to Acapulco from Manila, they didn't have any stopovers and it was a 5-7 month trip. So there was really no reason to be here except for the mission: they had started it, and they wanted to continue it."

|

|

|

|

"A lot of people who practice traditional agriculture, which is for subsistence," Rufo concludes, "they still do backyard gardening. They grow bananas around the house, papayas, taro, yams, they still do that. I still plant seasonal plants, and then I have my long-term plants like bananas, taro, tapioca, yam. I do it mostly to give away." But many other traditions remain. These are discussed in the next chapter, Footprints.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Inarajan Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||