|

“In Hawaiian culture,” Donovan explains, “the measure of a chief’s wealth often depending on his ability to be able to feed the people. The more folks that a chief would be able to feed showed great mana and ability to lead. In this current situation we find ourselves in, we see mono-cropping and industrialized agriculture, really falling short as far as being able to supply the current populations across the planet with nutritious, adequate food.

Three lovely large ‘umeke (bowls) for chiefs. National Museum of Natural History collection.

“The whole reason behind Hawaiians being able to have a four-hour work day was all of the work that they did, committed to producing food. And we just don’t put that kind of energy towards it. Based on the ships’ logs of the European travelers who first came to Hawai‘i, we know that the infrastructure that was here rivaled anything that they had seen in their societies in Europe.

"They acknowledge that the people here were able to produce food in an abundance that was unparalleled to anything that they had ever seen anywhere in the world. We know that what was established here that gave them that, was something that was produced over a millennia, let’s say presumably, thousands and thousands of years, that culminated in what the Europeans saw at the time of discovery in 1776.

“These explorers who came to Hawai‘i in the 1700’s wouldn’t have written what they wrote if they didn’t see the significance in it. It is shocking, because in one sentence they will acknowledge the greatness, and then in the second sentence reduce all of what they’ve recognized to nothing more than the ambitions of savages. Now these savages were able to produce all of this food but...nah, can’t possibly be better than what we did because they didn’t do it with steel. No, they didn’t do it with steel, they did it with stone, they did it with wood, they did it with their hands and they did it better than they were able to do it by their own acknowledgement rivaled anything that they’ve seen in western society.

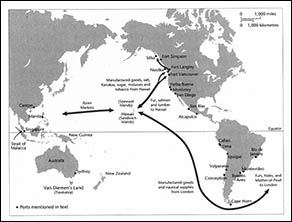

Map of Hudson's Bay Trade. From Mackie, Trading Beyond the Mountains.

“We know by looking at the historical shipping logs that during the early 1800’s, Hawai‘i was an abundant producer of food. The United States received tons and tons of food annually from Hawai‘i: sweet potatoes, regular potatoes, sugar cane, kalo, bananas, fish like you couldn’t believe. We were a huge, active salt producer here. During the 1800’s, the North American fur trade and the Siberian fur trade contributed their success to the ability to collect salt from Hawaiian salt makers. Hawai‘i being the number one stop in the routes going across the Pacific from the northwest and Siberia, we provisioned their ships, got all the salt to salt all the meats and furs that were coming out of those regions and being taken around the Cape Horn of Africa through the Pacific and over to Europe."

“Get plenty resources!” says Uncle Tom. “Then we can live off the land over here. I live off the land for quite some time, you know, raising your own stuff: your vegetables, your chicken, your pig. But most time we live on the turtle meat and the fish at that time. You cook them in different ways to make them appetizing, and that’s how we lived, the old life with the old people.”

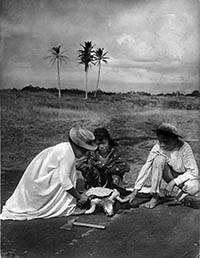

Hawaiian women preparing turtle. Hawai‘i State Archives photo.

“Our meat was the green sea turtle,” Nalani agrees. “My grandfather, Dad’s father, used to harpoon the green sea turtle, and that was our meat. You could make it a steak, you could make it stew. The wings, they would boil it to make soup. But basically, you could marinate it like teriyaki beef and it was good meat. It really is delicious. In the early seventies, the restaurants used to sell turtle steak on their menus.”

“We did eat turtle,” Lahela recalls. “It’s fabulous. You know its moderation, and then we share with families. But it was still legal during that time we were eating, the boys, my brothers.”

“But number one was fish. Fish raw, fish pulehu [grilled], boiled fish. Raw was number one. I’m a fish girl. We are known for the nenue fish because it’s a very strong tasting fish, if you don’t clean it for the stomach area. You got to gut them early so the stomach doesn’t smell, so people can eat them. That’s my fish place is the stomach area. I don’t care for the meat, just from the head up. I like that part. Like my mom. Certain fish we can eat the fish guts. Like for manini, the kala, the nenue, no way you can eat the guts, but certain fish we still do, raw or cooked. So fish, poi, was, I think for us, was our strength in our family. Also for fishing and still today, our family still help others catching fish for them and for the kūpuna, our elders.”

Nenue.

“Us over here was the nenue fish,” Uncle Tom says. “Everybody go, always get. You put inamona, but there was a special way you do them. That’s why I say, you got to get protocol. Because if you’re going to do them like any other ordinary person, going to be hauna, going be smelly. Because you got to do them clean and put the inamona inside—the salt, got to be right, and stuff like that. You know, there’s always something that we do here is different.”

“Now I like to fry nenue,” Samson says. “Put the shoyu and garlic inside there. Any size. We fry em whole, no more filet, too much work!”

“For our dinners we always had fish, I can tell you that,” Nalani concurs. “Both of my grandfathers were fisherman, so was my Dad. So there was always fish. Fried or pulehu, because if you caught a lot, then you can dry it to keep it.

“Pulehu was done on a fire,” Nalani explains. “They would always make a fire. They didn’t have a grill thing like what we have now, just like a piece of chicken wire, because people used to have chicken coops to raise chickens for their own eggs. Take a chicken wire and put it over the wood and then you put your fish on it. That was one other way to cook fish besides frying.

Pulehu (grilling) kala. Guy Holt photo.

“And if they dried it, you could eat it. If it was dry or half dry you could still eat it. We didn’t have drying racks like they do now, a dry box. Back then, they would salt the fish heavily with Hawaiian salt and hang it on the clothes line. That’s how my grandparents used to do it. They would tie the tails and then just sit it like that, or pin it. It depended on what kind of fish and how they cut it. They would tie the tail and then hang it them the clothes line like that."

“Akule, what they do, they lomi it, like the salmon,” Uncle Tom explains. “Like now it’s a modern way, they go cube them, but before it’s not like that . You lomi that thing. The onion is not sliced, you got to lomi that thing! And you lomi that, I tell you it’s a little different because it’s tasty, because of the water. When you lomi the onion, you going lomi the onion first and then you put the salmon inside there and lomi more. When you go lomi the onion, the water come green, tasty onion taste and with the salmon it’s tasty.

Lomilomi ("massaged") salmon.

"They cut them in in cubes, mash them like that with your fingers, and put them inside there, with your little gravy—water and salt—and if the salmon is salty, it’s okay, but if not enough salt, you go add salt, Hawaiian salt. And that’s how they’re going to eat them. It’s ono! Because the water in there, like if you put ice water inside there its better yet, its kind of iced down. Not like before, no more ice, so you just make them with water and salt. And you eat that with your poi. And it’s ono.

“The old people, I don’t know whether to say they wanted to stretch it and make a little bit more, I don’t know. But at the time, that’s how they eat that thing. That’s where the ono is, and most time they ate with a bunch of people. More appetizing we eating with people than only by yourself. Because everybody eating the same thing. Plus you get stew on the side, you get boiled fish, you get fried fish, everything right in front of you. You get dried fish, they get everything right there with the bowl of poi and the rice. Today you get the rice. And then after that you going to drink coffee and maybe saloon pilot cracker.”

“Akule was always a favorite,” Nalani agrees. “Or ‘oama, pāpio, ‘opelu. Nenue if was if it was made raw with a lot of kukui nut, limu kohu. That fish is known to be made raw, or you can fry it, you can make soup. That and kala, those were good fish for soup. Not soup with a broth, but soup just utilizing oil and shoyu with a lot of garlic and ginger. It was really good. The kala they used to dry it half-dry, and then you could fry it. A lot of the fish, if it was dry-dry, then you would just eat it like it that. If it was half-dry you could either pulehu or you could fry it.

Kala, a unicorn fish, off Hā‘ena.

“Half drying made it keep it longer. But the best way to keep the fish longer was if you really dried it. For a lot of them back then, dried fish was like candy. You could take it anywhere with you and just eat it like that. And you had a bowl of poi. That’s what you’re going to carry with you to the beach: pa‘akai, chili pepper and the bowl of poi.

You catch your fish, or you go get the he sea cucumber, the loli. I would see them clean it at the ocean, and some people would marinate it, like in vinegar. Some would cook it, but it just didn’t catch me.”

“I love manini, that’s another one we get,” Lahela says. “I love āholehole, I love it when it’s big and we love it raw. We get moi. Mullet, we can get river kind or the salt-water ones, they are very different tasting mullet. Even āholehole: there is river āholehole, and there is ocean. They are two different tasting. But number one is nenue.”

Āholehole.

“Certain fish guts, my Mom taught us how to ferment, with salt or garlic. If your manini was fat, you clean them and you throw the guts all in a jar. And nenue was another one, that’s the two most common fish, and the akule, we know how to do them now. But not everybody can eat like that. Almost like making palu, very similar like that, but with salt and garlic so it has flavor. And you let it ferment. You don’t have to leave them outside, we put ours in the ice box and it can stay for one year.

"Only a few of us can eat it—the old timers, they saw their parents eat, they know when they see it. It’s interesting because it’s learning from my parents. I was grateful that my Mom let me watch so I could learn. Because I want to eat them.”

“For me growing up, everything was canned,” Nalani points out: “deviled ham, spam, corned beef, Vienna sausage, those were the things we grew up on. Fish I will never give up, and being raised on reef fish, that’s something I won’t give up. Frying, that’s how I like, or dry fish, but by giving up all the other canned meats, the canned gluten stuff, I can do without it, I really can.”

Poi brought to the workday lunch at the loi.

“Our family was raised with poi,” Lahela recalls. “To this day I can eat poi, breakfast, lunch, dinner. It’s a little different now because we’re struggling to farm and to have the time to spend opening up the farm. So we’re trying our very best to open it up so we can have our own poi and not be buying poi.”

“Poi, that was the main starch,” Nalani reiterates. “My grandfathers: poi, not so much rice, it was more poi in the house.”

“Ulu [breadfruit] was not one of our table foods,” Lahela continues. “Taro was number one. My parents only used ulu to make for desert, like for baking when it’s ripe. When I got older I knew how to prepare ulu, and today I can still prepare it. I like it now, to change it up. But poi is number one, and whole taro, just sliced.”

Saloon pilot crackers, introduced by 19th-century sailing ships.

“Sometime for appetizing, if you want something in the afternoon, like snacks, you know what they would eat?” Uncle Tom asks. “They would make sugar water, break all the saloon pilot cracker in there, and eat it like that. The Hawaiians called it pokewai, and it’s ono. I no kid you. We eat that all that kind of stuff. Broke the darn thing in the koko, the saloon pilot, bust them all up in the koko and then eat it. Because that’s what had at that time. According to what we had, we could get in the store. Because no had super market over here, was all home kind of stuff.”

“Desert?” Lahela asks. “Yeah, we don’t have desert. No desert. It was the main meal. After that, no more room!”

“Over here it was great life,” Samson smiles, “I mean, my parents make sure we had plenty to eat. I never did hear my parents say, “Oh get more guys to eat.” Never, they just make sure plenty to eat.”

“One of the things about food production for Hawaiians was the energy—mana: what we produce we put mana into it,” Donovan concludes. “We put the life essence of our Creator into what we produce. Hawaiians have this tradition that when we sat down at the table to eat and Grandma takes the cover off the poi bowl, all speaking stops, and no ill words are spoken during that time, because food absorbs the mana. And we will sour the poi with sour words. And essentially it’s the same with what we produce. As we produce, if our thought is not pure, if our intention is not pure, then even if the food is good, even if what we produce is good, it’s still sour. We don’t think about those things.”

|

|