| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Come land your canoe at He‘eia.

|

|

|||||||||||

|

“Kāne‘ohe bay was settled early and was favored by the in-migrating Tahitian chiefs,” Kalani states. “They settled in. Kāne‘ohe was the initial capital of O‘ahu, as well as Kailua and Kualoa. The fertility, plus this is the largest bay in all of Hawai‘i. Bigger than Pearl Harbor. So it offered very fertile land, good fishing, sheltered waters. It was just ideal for settlers.” “When the blue-blood chiefs of Tahiti came here and settled, they settled here on the windward side,” Emalia adds. “Kāne‘ohe Bay was where they set up and the reason for that is that the water was plentiful, it came through like a sieve in the Ko‘olau. It’s like a sifter really, filters out all good water. They had lots of fresh water, lots of good soil because this area is good for raising plants and crops, and then they had the bay. The bay was full of fish and seaweed so they had everything they needed.” “Kāne‘ohe Bay is also associated with the voyaging saga of a family of chiefs,” Dennis writes, “which included Mō‘īkeha, his son Kila, his heir La‘amaikahiki, and his grandson Kaha‘i. These chiefs appear in the genealogy of Nana‘ulu (Kamakau Tales 76-77), on which chiefs of Maui, O‘ahu, Kaua‘i, and Ni‘ihau trace their ancestry back to Papa and Wākea: 1. Wākea and Papa “‘Ulu and Nana‘ulu were sons of Ki‘i, who appears 13 generations after Papa and Wākea; the genealogies that flow from these two brothers run parallel to each other. Mō‘īkeha’s grandfather was a chief named Māweke, who appears 15 generations after Nana‘ulu, making him a genealogical contemporary of ‘Aikanaka, father of Hema. The sons of Māweke ruled O‘ahu Mulieleali‘i in the southeastern district of Kona (Fornander Ancient History 48) or ‘the western side’ of O‘ahu (Kalākaua 118); Keaunui in ‘Ewa; and Kalehenui in the windward district of Ko‘olau (Fornander Ancient History 48; Kalākaua 118).

"The traditions of Mō‘īkeha and La‘amaikahiki have been published in Fornander (Vol. IV, 112-128), Kamakau (Tales 77, 105-110), and Kalākaua (117-135). The broad outlines are consistent, but the details are various: Kalākaua identifies the homeland of Mō‘īkeha and La‘amaikahiki as Hawai‘i; La‘amaikahiki was a high chief of O‘ahu and an adopted son of Mō‘īkeha. The Fornander version says that Mō‘īkeha belonged to Tahiti and that La‘amaikahiki was Moi‘ikeha’s son by his first wife Kapo. Kamakau presents two versions. First, La‘amaikahiki was a high chief of O‘ahu, born to Ahukai and Keaka-milo at Kapa‘ahu in Kūkaniloko, Wahiawā, the sacred birthing place of O‘ahu chiefs. “This chiefly child was ‘taken’ by Mō‘īkeha, perhaps in an attempt to control the future ruling chief. This taking seems to have provoked an attack by his older brother Kumuhonua, and a sea battle was fought between Kumuhonua and his younger brothers ‘Olopana and Mō‘īkeha. (Conflict over land and the right to rule between the senior and junior lines of a family is a common motif in Polynesian and Hawaiian chiefly traditions; Kalākaua says that ‘Olopana and Mō‘īkeha left O‘ahu because they were not satisfied with their prospects under their older brother.) "Kamakau gives a second version of the story, in which Mō‘īkeha belonged to Kahiki and La‘amaikahiki was a chief of Kahiki whom Mō‘īkeha, after he settled in Hawai‘i, designated as his heir. Whatever the case, La‘a, whose name means ‘Sacred One,’ possessed great mana. The voyaging back and forth between Hawai‘i and Kahiki is motivated by the need to obtain his mana. “All the stories agree that at some point Mō‘īkeha, ‘Olopana and his wife Lu‘ukia, and La‘amaikahiki were together in Tahiti or Ra‘iātea, an island 120 miles WNW of Tahiti. Mō‘īkeha departed for Hawai‘i after some unhappy experience: either he was frustrated after a man named Mua slandered him and his lover Lu‘ukia refused to sleep with him anymore (Fornander); or he was caught undoing Lu‘ukia’s chastity belt (a sennit lashing) for which he was ‘severely criticized’ (Kamakau Tales 105); or ‘Olopana was jealous of his younger brother’s increasing popularity and influence, and rebuked Mō‘īkeha publicly for his ‘extravagance and love of display’ (Kalākaua 121). Dennis explains the concept of mana, and its connection to voyaging “Whatever his reason(s), Mō‘īkeha left the southern islands and arrived at Hawai‘i Island, then sailed downwind across the island chain and settled in the Puna district of Kaua‘i (at Kapa‘a or Wailua). He learned of a sailing contest to win the right to marry Ho‘oipo, the daughter of the chief of Puna. The contest was open to ‘all of noble blood.’ Mō‘īkeha chanted his genealogy from Wākea down to his grandparents Maweke and Naiolaukea and his parents Mulieleali‘i and Wehelani, ruling chiefs of O‘ahu (Kalākaua 128); thus, he was allowed to enter the contest.

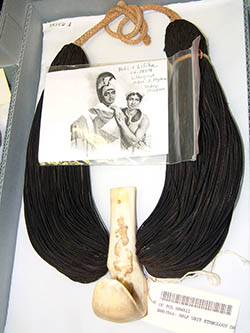

“And he won by beating his rivals to the island of Ka‘ula 22 miles SW of Kaua‘i and bringing back a palaoa (whale tooth) from the chief’s representative, who had been sent there earlier. His victory was assured by La‘amaomao, the god of the winds, who had come with Mō‘īkeha from Ra‘iātea and who carried an ipu, or gourd, from which he could call forth winds favorable to his chief. “Mō‘īkeha became the ruling chief of Puna after his father-in-law’s death. As he grew old, he longed to see La‘amaikahiki, the son (or foster son) he had left behind in Kahiki; or he wanted to bring his designated Tahitian heir La‘amaikahiki to rule his lands in Hawai‘i. Mō‘īkeha held a contest to determine which of his five sons would get the honor of sailing to Tahiti to bring La‘amaikahiki back (Fornander). Each of his five sons tried to send a kī-leaf canoe downstream between his thighs; only the canoe of Kila hit the mark, revealing his knowledge and understanding of the winds and currents in the stream and establishing that his mana was greater than that of his brothers. He was chosen to head the expedition south. “Kila reached Tahiti and brought La‘amaikahiki back to Hawai‘i (Fornander and Kalākaua); or ‘Olopana refused to let La‘amaikahiki go to Hawai‘i, as this young ali‘i was also heir to lands in Tahiti; but after ‘Olopana’s death, La‘amaikahiki decided to sail to Hawai‘i because he had heard about the fertility of the land and the industriousness of the people (Kamakau). “So sacred was La‘amaikahiki, he had been hidden away in the mountains of Kapa‘ahu (Fornander). Kila was required to make a human sacrifice before he could enter the marae, or temple, where La‘amaikahiki was worshiping his god Lonoika’ouali‘i (‘Lono of the royal supremacy’ or ‘Lono in the chiefly signs in the heavens’). La‘amaikahiki brought this god to Hawai‘i. Lonoika’ouali‘i was the god worshiped by the Mo‘o Lono (the hereditary order of Lono), one of two orders of kahuna, or priests, maintained by the 19th century king, Kamehameha I, who was the last ruling chief to worship the ancient gods: ‘Their rituals were those of the god Lonoika‘ouali‘i, the kapu lama [ritual to obtain lama trees to build fences, houses, and towers in an agricultural heiau?] and the kapu loulu [ritual for dedicating a heiau to insure peace and prosperity; loulu palm leaves were used for thatching], which were heiau rituals. Lonoika’ouali‘i was the visible symbol [image] of the god Lononuia kea [‘Great, broad Lono’]’ (Kamakau People 7; cf. Kamakau Works 130-144; Ii 33-45; Malo 159-176).

“Besides introducing the god Lonoika‘ouali‘i to Hawai‘i, La‘amaikahiki also brought the pahu hula, or hula drum, and traveled about the islands teaching the art of dance accompanied by the drum (Fornander). The drum was noted for its loud voice, like the voice of a god, and hence embodying great mana. The drum brought from Tahiti by La‘amaikahiki was heard in the trade winds at Hanauma Bay as La‘amaikahiki’s canoe crossed the Ka‘iwi Channel between Moloka‘i and O‘ahu; it was heard at Makapu‘u as the canoe entered Kāne‘ohe Bay (Kamakau Tales 109). As a receptacle of the voice of the gods, the drum was eventually used in religious ceremonies and accompanied the most sacred dances:

Keola Dalire discusses hula traditions of He‘eia “Kalākaua emphasizes La‘amaikahiki’s genealogy as the source of his mana: ‘In his veins ran the noblest blood of Oahu. He was the son of the great grandson of the great Paumakua in direct and unchallenged descent’ (133). After La‘amaikahiki settled at Kualoa on the north end of Kāne‘ohe Bay, the local chiefs found three wives for him. And in a great display of procreative mana, three children were born to him, all on the same day: Lauli-a-La‘a by Mano in Kāne‘ohe; Kūkona-a-La‘a by Waolena at Ka‘alaea; and Ahukini-a-La‘a by Hoaka-nui-kapua‘i-helu at Kualoa (Kalākaua 134-135; Kamakau Tales 109-110). “The locations of the homes of his three wives, from the south end of Kāne‘ohe Bay to the north, suggests a generous spreading of his mana over the surrounding area. “After the births of his three sons, La‘a returned to Tahiti to rule over Mō‘īkeha’s lands there (Fornander); or to Ra‘iātea to rule over ‘Olopana’s lands (Kalākaua; Kamakau does not report what happened to La‘a after the triple marriage and triple birth). Fornander says that after Mō‘īkeha’s death, La‘amaikahiki returned to Hawai‘i a second time to take Mō‘īkeha’s bones back to the ancestral lands in Tahiti; but through his children, he left his mana in Hawai‘i, becoming an ancestor to the chiefs of Hawai‘i, Kaua‘i, and O‘ahu. ‘You will find his chiefly descendants in the mo‘o kū‘auhau (genealogy) of Nana‘ulu, Puna-i-mua, and Hanala‘a-nui’; Mō‘īkeha’s son Lauli-a-La‘a, appears in Kamakau’s genealogy of Nana‘ulu (Tales 78, 110). And ‘From Ahukini-a-La‘a Queen Kapi’olani, wife of Kalākaua, is recorded in descent through a line of Kauaian chiefs and kings’ (Kalākaua 134-135). “At the end of Waiakalua Road, on the southern end of Kāne‘ohe Bay, is a small beach park where hau trees grow along the dark brown sandy shore. A portion of this beach is named Nā One a La‘a, ‘The Sands of La‘a’ When La‘amaikahiki’s canoe arrived at Waiakalua from Hale-o-Lono, Moloka‘i, a man named Ha‘ikamalama chanted the mele of his drummer Kupa (which Ha‘ikamalama had heard in the wind at Hanauma Bay and at Makapu‘u as La‘amaikahiki’s canoe sailed to Kāne‘ohe.) Surprised by the man’s knowledge of the chant, La‘amaikahiki ‘threw down some sand as a resting place for the canoe’ and landed. The place name commemorates this landing. Ha‘ikamalama was allowed to play the pahu of Kupa and made a copy of it: a gourd fitted with a shark-skin head. (Pahu were later made from hollowed-out coconut trunks or breadfruit logs as well.) Near Nā One a La‘a was the house where La‘amaikahiki once lived; and on a low hill nearby was his heiau, called Kalaoa (Sterling and Summers 209-210).” |

|

|||||||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

||||

|

||||

Copyright 2019 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

||||