|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

“The Hawaiians didn’t really believe in private property in terms of the land,” Kalani points out, “because no humans could own mother earth. So the land was taken care of by humans but not 'owned' or abused by humans. Mankind were temporary caretakers of the land, and had to respect the land because after all, you mālama the ‘āina, you take care of the land and it will take care of you.”

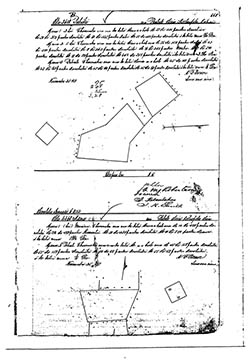

“The commoner portion, the little bits of things that they got—roughly about 2 acres a piece, maybe 2.5—they were surveyed,” Lilikalā explains. “The total amount that was surveyed was about 8,500 awards that went to the commoners. They made about 29% of all the land in Hawai‘i. But that’s not that much considering the rest of the land. “The surveyors were Punahou [school] teenagers who had been trained by missionary parents on to how to do survey. They were sent out to do survey. Some were accurate, some not so accurate, but they didn’t have enough people to do survey. And they made all the commoners go get survey. “At the same time the Land Commission was doing this, the missionaries were petitioning to buy land. As soon as they got everything divided up, which was the rush in 1852, then they allowed foreigners to own land. Missionaries paid 50 cents an acre when the land was going for a dollar an acre for pasture land, two dollars an acre for taro land.

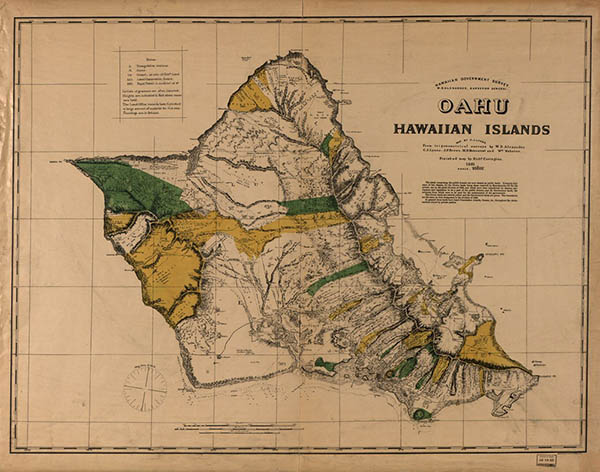

“They paid 50 cents an acre. Like the guys who got Kualoa, that’s missionary land that became the Judd spot, that land up there, and it’s now owned by the Morgans, who are descendants of the Judds. Kualoa Ranch sold at 50 cents an acre. “And then a lot of commoners came forward to pay $1 or $2 an acre to buy land, so commoners also bought land besides missionaries. But missionaries would buy, on average, 590 acres a piece for 50 cents an acre. I don’t know why that’s the magic number, but that’s what I saw over and over again on missionary records, in the land records. “Now the guys who ran that Land Commission knew that you could not become wealthy capitalists with two acres. They knew that you had to have 590. If they were really trying to turn common Hawaiians into agriculturalists who would make a lot of money, and become capitalists—because that’s what Calvinists were all about: you could become a Calvinist if you followed this way and you did private ownership of land. You could be po‘e waiwai as they called it, rich people, like white Americans. It’s about how much land did you get. “Not even the chiefs understood capitalism except for one: Ruth Ke‘e-liko-lani. She was a hānai daughter of Ka‘ahumanu, and she understood that land could equal money. She seemed to be the only one who did. But because she went around collecting all the lands of her relatives who were dying without heirs, she ended up with something like 18% of all the lands of Hawai‘i, which she gave to her cousin, Bernice Pauahi. Upon Ke‘e-liko-lani’s death, she gave to her cousin, and that became Kamehameha Schools. So the only chief who understood capitalism, really, was the chiefess who put together Kamehameha Schools’s land.” “All of He‘eia went to Bernice Pauahi’s father, Abner Pākī, who got it from Kamehameha III in the Mahele. He didn’t get it through Ke‘e-liko-lani. This is one of the lands that descended to Pauahi from her dad, and some came from her mother as well. So Ruth played no role in this one. “I suspect that was because he was really good at taking care of fish ponds. It seems to me that if I were to look at all the fish ponds in Hawai‘i on the various islands, Pākī seemed to get lands that had fish ponds in them. Which, to me, means that he was part of a mo‘o family that taught about what you do to take care of fish ponds. That knowledge is not shared widely with everybody. It’s kept in certain families. “It seems to me he was awarded a lot of ahupua‘a where fish ponds were. There’s 252 chiefs in the Buke Mahele. They are not all the chiefs of the land. They are the chiefs most closely related to Kamehameha. There are ten high chiefs—ali‘i nui—and Abner Pākī was not one of them. He was the next level that I am calling kaukau ali‘i, second-grade chiefs. And then there are konohiki under. There’s about ten ali‘i nui, 24 kaukau ali‘i, and the rest I think it’s 218, are konohiki. These are what we used to call ‘land managers,’ but I’m calling them ‘water managers’ now. And you would have different layers of them. In my book Native Land and Foreign Desires, in one of the last chapters, Moment of Mahele, there’s a breakdown of each of classes of konohiki. There are high konohiki who would be in charge with several ahupua‘a on different islands under a high chief or kaukau ali‘i like Pākī. “Pākī wouldn’t actually do all the management on all the land he had. I think he had about 40 ahupua‘a; he got 20, the king took the other, so they split about 50/50. That was the rule, but he had different levels of konohiki managers. Now, those konohiki or water managers would be lesser-lineage relatives of the chief who got the land. They are probably not the people who ran that fish pond for the last ten generations. They would come with the high chief that got the land in 1848. It looks to me as though most of the fish ponds were given out to some level of chief, either an ali‘i nui or kaukau ali‘i, a high chief or second-grade chief, and not given over to the king to give to the government.

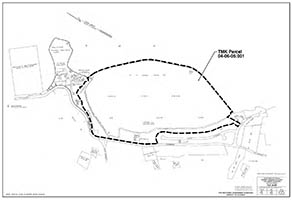

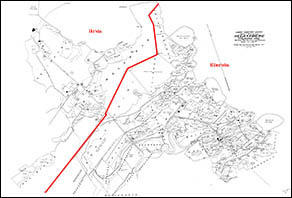

“The idea was in the Mahele, the king was going to collect all of these lands and put them in a pot of lands for the commoners to choose from. But what actually happened was the land commission was run by missionaries, William Richards in particular—Calvinist missionaries—and what they did was they allowed all the commoners to come and claim lands no matter where they lived. So, even though Pākī got the whole ahupua‘a of He‘eia from mountain to sea and into the ocean, there were commoners who lived here and who came to claim land. “Same thing with Kāne‘ohe. Queen Kalama, who was also a kaukau ali‘i, got all of Kāne‘ohe, and there were lots and lots of commoners living there, lots of people with taro gardens who came to claim the land. Nobody did it by measuring the exact acreage of the ahupua‘a. They just said, ‘Oh, this is the boundaries of ahupua‘a. We know where they are. This one goes to this chief. This one goes to that chief,’ et cetera. "And then when you have high konohiki, some of them got an ahupua‘a. But most likely, they got a portion of the ahupua‘a like an ‘ili. It was complicated and they did it without a map. So it’s a map of their mind.” “A lot of the kuleana that reside within this area were under the family Ka‘uhane,” Rick says, “And to this day, they still have about an acre of land, landlocked within this now Kamehameha School’s parcel.”

|

|

|||||

|

The changes in land tenure brought by the Mahele underpin the issues that continue to affect He‘eia. Next we read about the aftermath of the Māhele in this ahupua‘a.

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

||||

|

||||

Copyright 2019 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

||||