March 02, 2016

The ‘iako, or booms, lashed to the hull of my canoe. Where my hull has reinforcements around the holes that the ropes pass through, an old Hawaiian canoe would have pepeiao—ears—carved into the hull, to hold a cross brace called a wae.

Lashing this canoe together needs to be quick and efficient. I say this because I drive a VW golf. With my roof racks, I can strap all the canoe parts on the car and drive to the Chesapeake Bay in half an hour. It takes maybe another 30 to 45 minutes to unload it, lash the whole thing together, and rig it. I can sail for a few hours, come back, take it all apart, put it back on top of the car, and drive home. For two to three hours' sail, it's worth it. Ahhhhh. But it means that I'm always putting the canoe together and taking it apart.

The lashing of a canoe is both an art and a science. The lashing needs to be strong enough to hold the craft together in rough seas, it must be tight so the pieces can flex but don’t wobble, and it can be beautiful as well.

There are two sets of lashing required for a small canoe like this. The first is connecting the booms (‘iako) to the hull, and the second connects the other ends of the ‘iako to the ama, the outrigger float. How these connections are done depends on the configuration of the canoe. On the Hawaiian-style canoe, the ‘iako are lashed to the hull using two projections called pepeiao—ears—carved on the inside of the hull. These projections have holes through which the rope can pass and are used for anchoring U-shaped braces called wae that span the hull. By projecting, the pepeiao provide much more room to lash the ‘iako and give greater stability.

Left: Pepeiao on the Kapi‘olani canoe, carved out of the hull itself. Right: The brace and lashing of the ‘iako on the NMAI's much more modern ‘Auhou canoe. Note how the U-shaped wae is lashed to the pepeiao.

Lashing my canoe did not involve these wae braces, so to better understand Hawaiian canoes, I went to my canoe-building friend Jay Dowsett of the Friends of Hōkūle‘a for a lesson.

Jay Dowsett, a canoe-builder and member of Friends of Hōkūle‘a.

Jay Dowsett, a canoe-builder and member of Friends of Hōkūle‘a.Jay demonstrated on a modern fiberglass canoe, using a block of wood in place of the ‘iako. This is based on examples of old canoes. It seems a little tricky, but Jay assures me that doing this repeatedly is what’s going to teach you. First time is a learning curve, second time you’re pretty much getting it down, and by the third time you’ll be teaching it. He explains while I assist him:

This length of line is a total of 12 fathoms, and we then split the difference, put a loop in the center, and then we feed the loop around the wae, and then the two ends that you actually use for lashing through this loop. Then you try to tighten it up so that the ropes are coming off the bottom of the wae.

Now most people are under the impression that you’re using cotton cord because cotton shrinks when you wash it, but it’s actually the opposite: Cotton swells and gets thicker. It’s the swelling action that makes this tighter and tighter. Yes, when we do the lashing, the lashing is going to be very tight, but once it gets wet and starts to swell, that’s what really makes it bulletproof.

To begin lashing an ‘iako (boom) to his modern canoe, Jay folds 12 fathoms (72 feet) of cotton rope in the middle, then pulls the two ends of the rope through the loop in its center. In this fiberglass canoe, the wae (cross brace) is built right into the hull, but the method and principle are the same.

Jay and I stood on opposite sides of the canoe worked one of the two ends of the rope. I followed what he was doing as he talked me through the steps:

We’re going to do a series of cross-overs to hold it down. The rope comes over the back and goes forward, then through that hole. I’ll do the same.

A lot of people, when they first start rigging, they want to pull as tight as they can on the very first time. You can’t. What’s going to happen is, when you pull, the whole ‘iako is going to get shoved backwards. So doing the first one is a little tough as far as getting it really tight.

Then you go underneath the ‘iako, over the top, and through the back hole.

Clockwise from upper left: Jay seats the knot of the loop at the bottom of the wae. We each bring an end of the rope over the ‘iako and thread it through a hole on our side of hull. Once outside the hole, we loop the rope around the ‘iako, then thread it through the other hole on our side of the hull. Then the rope loops back over the center of the wae and goes to the opposite side, and we follow the same steps again.

We’re going to repeat this whole process over and over again until we run out of line. Now the key here is that someone is going to be considered first, and someone is going to be considered second. That means someone has to start the lashing, and someone has to follow.

Every time I go, I’m going to go behind this loop that you first put in, and then you’re going to go behind the loop after me. Then you’re going to come across and you’re going to lock me in. Bang, bang, bang, bang—these keep locking each other in. This loop is going to keep the rope from getting pulled over to my side. Now, you’re going to do the same thing. Now you can pull it as tight as you can manage.

Now to make it look pretty, you see where it crosses over, you don’t want to do that haphazardly anywhere. You want to try to keep it looking good, and keep it in the center. So as you cross over, all of the cross bars will be in the center. And then there’s always the question of, are we lashing to the inside or to the outside? That is, every time we cross over, are we going to be on the inside of the rope or the outside of the rope? In this particular case, we’re going to the inside, so each time we do it, we’re going to be moving closer and closer to the center. And there is method to this madness—you’ll see why.”

We continue following the same pattern. For the sake of this example, we will go around four times, but seven or eight is normal. It’s all repetition up to this point, following the same pattern and keeping it neat. Then we switch to just wrapping it four times with each end of the rope.

Then we switch ropes and take them straight over the top, again wrapping it four times with each end of the rope. Normally we would be pulling it very tight each time. After the fourth cross-over, we switch ropes.

For this demonstration, Jay and I did four rounds of lashing, as opposed to the more typical seven or eight, then wrapped each end of the rope over the center of the wae and ‘iako four times.

Now we go through and around those vertical loops we just made. Each time, we switch and take each other’s rope, then do it again. We are just wrapping—frapping, it’s called—the binds to pull them tight together. That tightens it all up and draws the 'iako down tight.

At the end we pull against each other, and that tightens it all up and pulls it down. Now we tie it off with a regular square knot. Normally I would tie the square knot on the other side. We shove the ends through and tie the knot on the other side.

Clockwise from upper left: To “frap” means to “tighten the slack.” This is done by wrapping the rope around the previous loops and “choking” them very tight together. The lashing is tied off with a square knot.

Then the excess—if you want, you take it around a couple of times and bury it. Or we can attach a bailer to it with a slip loop, so the bailer is hanging right there handy.

Now with the bigger boats, you’d just go with a straight clamp down, just clamp it down as tight as you can, but do it in several spots. And the way the lines were run, you’d come across and do figure eights. You’re talking about 16 or 20 wraps each time, and then you start getting into a figure eight wrap. That frapping then takes that whole rope and turns it into something like a solid piece of wood. When you knock on it, it sounds like a piece of wood.

Above, left and right: Jay demonstrates making figure-eight bundles.

You will notice that Jay’s lashing weaves an attractive geometric pattern where the ropes cross each other. This, it turns out, is not just for looks. It actually locks down the ropes each time, making for less chance of catastrophic failure. I witnessed this after riding on a contemporary outrigger with folks from Windward Community College on O‘ahu. As we were putting the canoe up, we noticed that someone had vandalized the lashing by slashing it. Nonetheless, it had held together. “I’d like to have met the people who figured out this geometric pattern over time,” Jay says, “because those guys were geniuses. It was probably guys, because canoes were a male-dominated activity.”

Left: The lashing on the booms of the Makali‘i voyaging canoe. Right: This vandalized lashing still holds together thanks to the interlocking pattern.

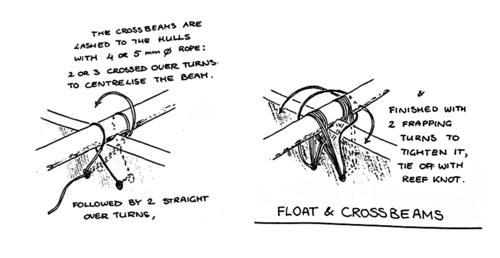

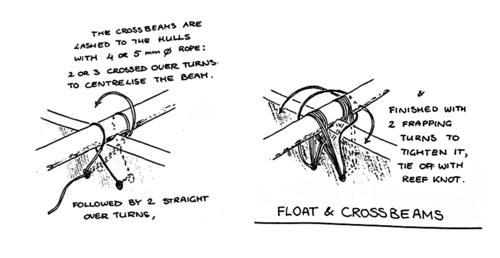

These drawings show how James Wharram, whose Polynesian design I've been following for my canoe, suggests lashing the booms. It’s a very simple, in-and-out, over-and-under kind of lashing, exactly as Jay demonstrated, but without the wae. The rope goes through a hole, loops around the boom, then through the other hole, then does the same on the other side. Then wrap it around the lashing to “choke” it tight, and tie it off with a square knot.

Lashing instructions from plans for the Melanesia, courtesy of James Wharram and Hanneke Boon.

And here’s what it looks like, finished:

The booms lashed to Doug's canoe.

It was a little confusing at first, and once in a while I still make a mistake, but mostly it goes very quickly. Now attaching the outrigger to the other end of the booms is an entirely different story, and the subject of my next installment.

—RDK Herman |