|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

The yard at Luakaha near the waterfall.

|

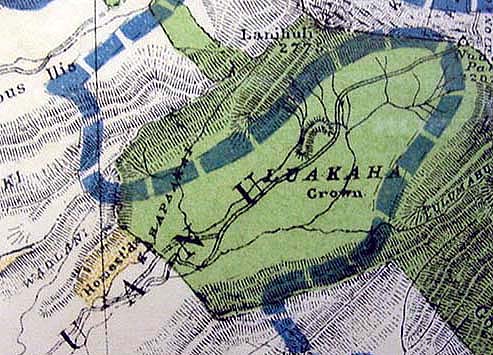

| The transition from the traditional land tenure system controlled by the ali‘i to a new one based on private property and "fee simple" ownership was not without problems. This new form of land tenure was well understood by the Western residents and visitors, but was alien to the Hawaiians. So too, the notion of "rights" had evolved in a particular, legalistic manner in the West, while the Hawaiian system was more characterized by "responsibility." These differences play out in the story of Luakaha. "The ‘ili of Luakaha," Stephen says, "was the upper half of the valley, all the way to the peak. And those were Crown Lands. And it would go back to the fact, remember, Kamehameha was the victor, and part of his legitimizing his role as the supreme chief would be to maintain control over the key ahupua’a."

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

"The ali‘i set that mauka part of Nu‘uanu valley as Crown Lands," adds Kalani, "and therefore belonging to the ali‘i family. Exactly how it changed hands…there’s always a story that goes with that! Usually somebody went in and saw someone and said, 'you don’t need that portion, so why don’t you give it to me, and this is what I’ll do for you.' "And suddenly you find carved out of what was Crown lands some private property—not by Hawaiians—and you just shake your head. The Hawaiians would not do that, because no one owned it, and you would always be able to use it, and along with use, hand in hand wedded, was taking care of it." The story of how the name 'Luakaha', once applied to the Crown Lands of upper Nu‘uanu, came to designates a private property just below Kaniakapupu, is told in the writing of Clarence H. Cooke (1938).

|

|

Some time in the late 1820s or 1830s, Kamehameha III hired a Captain Hinckley from Boston to repair the Pali Road, which at that time a was rocky and muddy track. Hinckley, known in Hawaiian as "Hikele," frequently asked the king for a piece of land in Nu‘uanu, to build a rest house for his wife and himself. The king did not consent, however, until finally Hikele made the following proposition:

The King then consulted with Kinau, the Premier of the Kingdom, and with the ali‘i. Then he granted Hinckley's request. This verbal contract was, according to ancient custom, stated to others whose duty is was to memorize it.

|

|

|

|

Hinckley wound up in debt to a Mr. French, whose interests were in turn bought out by British citizen, Mr. George Pelly of the Hudson Bay Company. Cooke (1938: 3) writes "Captain Hinckley gave t hem in part settlement all his interest in the lands of Nuuanu Valley given him, as he claimed, by the King. However, the chiefs did not recognize this assignment on the grounds that he only had an occupancy and not a title claim. The chiefs therefore took over the land, destroyed the house he had built and demolished the walls." But Pelly claimed that the property was assigned to him as part of Hinckley's estate, and complained to the British government about the Hawaiian Kingdom's action. His complaint reached fairly high circles. In 1839 the H.M.S. Sparrowhawk arrived in Honolulu and made a claim on behalf of Mr. Pelly. The King resisted for about a year, then Ka‘ahumanu II, the Premier, gave her consent, though her statement makes it clear that she felt Pelly was acting inappropriately.

|

|

|

|

|

|

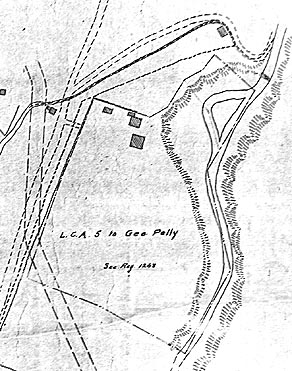

This story of confusion and mutual dissatisfaction is translated into the Mahele records: "Claim Number 5, George Pelly: This claim is of a peculiar character, being of that class which may be denominated forcible. It appears from the assignment that William S. Hinckley was in possession of certain unascertained premises and transferred all his right to William French, but what the right of Hinckley was that he thus transferred does not appear. The Board is therefore forced to believe it to have been a mere possessory right according to the usages of the country, and was only assigned in order of a temporary place of residence. However on a complaint of the British Government and the despatch of the British sloop Sparrowhawk to see him reinstated without judicial inquiry and without consideration ever paid to the King and the chiefs by the original possessor, Hinckley, the Board cannot go behind the act of the King and the Premier and their consent must be considered as one voluntary out of respect for the masters of the British Government, and since nothing appears to show actual compulsion the Board cannot question the King's and Premier's very acts regarding the soil."

|

||

|

|

||

| After a number of transfers, including into the hands of Prince Albert Kunuiakea, the property was finally purchased and deeded to members of the Atherton and Cooke missionary families, who retain it to this day. Now "Luakaha" refers not to the Crown Lands of the Hawaiian royalty, but to a private property owned by foreigners. The means by which this Royal Land—property of the King—became a foreign-owned private property demonstrates both the different concepts of property, and different notions about social obligation and responsibility. A loan, made hesitantly by the King, was claimed as private property by foreigners. It was the king and premier who then chose the path of courtesy by allowing this claim.

|

L.C.A. 5 to George Pelly.

|

|

|

"I find that to be true with all Hawaiians," Kalani remarks, "they are incredibly considerate of other people and their feelings. It is to their own detriment that they keep it up, because this kindness is something that is Hawaiian: we area very tolerant people. Rather than take issue with the newcomer who came in and probably tricked the family out of land in some fashion, they let it go. "But the Hawaiian knows, and the newcomer knows what has not been said, and that is, 'We know that something went on and we will not bring it up out of courtesy. You know that I know, so don’t think that you are getting away with it.'"

|

||

|

|

||

| This was not the first time that Hawaiian royalty would yield to foreign pressure and thereby lose land. In fact, this was just the beginning. We will hear more in the next chapter, Memories.

|

||

|

|

||

| |

| |

|

|

|

| Nu‘uanu Home | Map Library | Site Map | Hawaiian Islands Home | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||