|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| |

|

|

|

“World War II was a big fight on Palau,” Johnson laments. “A lot of people died. Some were shot. A lot of people were killed. It was a terrible thing." “The war was here for I think a good two and a half years,” Kathy says. “There was constant bombing and air raids. The Americans were bombing. And I think one of saving factors was they had a spy here, they knew which parts of Palau were Japanese installations. There were bombing those constantly. Koror was bombed extensively—it was heavily populated by Japanese."

|

||

|

|

||

"The communications center in Airai, that got bombed, and there were a lot of Palauans working there or living around that area. It was the main communication center for the Japanese and for the whole Nanyo-cho—the whole Japanese imperial administration, or something like that.—Yap to everywhere. It was an important place." “The Japanese dug a lot of trenches along the road in Airai, and up the hills,” Walter relates. “There are rolling hills all over parts of Airai State, so they cut trenches through there, and fox holes. The village area was bombed—it was really so close to the airport, which was fortified, that high point in Airai State. There were guns over there, on top of that hill. And on every mountain in Airai State, both on Babeldaob and parts of the Rock Islands."

|

|

|

“Even on the Rock Islands, they built gun emplacements along the bay of Airai and on the Rock Islands that face the land, facing from to the south and west sides of Airai Bay. They told the people to leave, during the war, when the war was on—to leave their homes and go to cave areas, or relocate to nearby villages in Aimeliik. And the Japanese took over the whole village. They lived in the bai, in the big old houses. It was a mess after the war.” “Everybody relocated to Babeldaob from Angaur and Peleliu and part of Koror” Kathy remarks. “They all moved to Babeldaob and stayed in caves. I’d say a couple of thousand Palauans were actually killed during the war. Mostly from disease and starvation. "There were some few who got shot from strafings because they went fishing. But a lot of the death was caused by the living conditions of the war: starvation, malnutrition. You couldn’t light fire during the day because you were afraid they might bomb, even at night.”

|

|

|

|

|

“I have two older siblings who died in the war,” Johnson recalls, “because they lived in the woods, they had no medicine and no food. Awful. It was an awful experience. People died left and right. There were air raids every day from Peleliu—they were bombing Palau. So you couldn’t cook anything in the daytime because the smoke would draw the planes. They cooked at night, and they tried to keep the smoke from going out. They were starving, and a lot of people died."

|

||

|

|

||

“Able-bodied young men were shot during the war, in the Rock Islands while they were fishing. Father Felix Yaoch—the Catholic priest, our cousin—his older brother was shot in the lagoon. There were shot during air raids. “The war had a big impact on Palauan lives. My mother, my natural mother has only one brother who died in Indonesia during WWII, and some Palauans were drafted and joined the Japanese and went to Indonesia and fought, and never came back. “My father was a police officer during the war, and my uncle Roman, who was Johnson before me, used to work for the kempeitai when I was a young boy. Kempeitai was like the Gestapo in Germany. He saw a lot of executions and things."

|

|

|

“The Spanish priests were executed by the Japanese in 1945, and my uncle Roman was a witness in the war crimes trial in Guam in 1947. He didn’t see them get shot, but he saw them going to the hills. The trial transcript was released in 1997 for the first time after 50 years, so we saw his testimony. And we realized that not only were the two Spanish priests and one brother killed in Palau, they brought a handful of additional priests from Yap who were also executed in Palau, at the same time. So it was a sad story. We don’t want to see that happen again here. “Recently, Professor Don Schuster from the University of Guam came here looking for their graves, because they were buried over the bodies of American airmen, who were executed before. They went to Ngatpang, and they couldn’t quite find them, because its overgrown there, but there is an ongoing search for their bones.”

|

|

|

|

“There was a number of Japanese people who died in Palau, and after the war you could see dead bodies all over the place, and nobody cared. There were some Korean and Japanese orphans who became Palauans because their parents just gave them to the local people. So when we became independent, they had to be adjudged Palauans, because they had no blood connection to Palauans, yet they were raised as Palauans. "It’s a sad story. Some families were split—half of the kids remained in Palau with their mothers, the others went to Japan and never came back."

|

|

|

"Around 1972 I was crossing the channel between Airai and Koror, and a Japanese guy on the ferry boat starts speaking Palauan to me! And he turned out to have lived in Palau most of his life until the end of the war, and left Palau to Japan with a few of his oldest children, and left behind the others—my cousins. And they never met their father, and that old man came back and he spoke Palauan. He came with his Japanese daughter, half Palauan, who couldn’t speak Palauan, and his kids would speak Japanese. “In the mid-80s, one of his sons went to Japan with the Airai chiefs and he met the old man. He was dying, and he held his son’s hand and died. There are many stories like that. Even our president Nakamura, he’d go to Japan as a kid, and when he went back after the war, he had to file petitions to the United Nations to return. Many kids were displaced.”

|

|

|

|

|

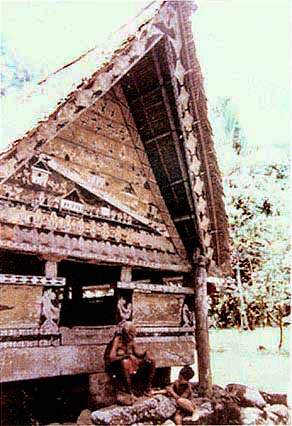

“A complete renovation of the bai, especially the roofing, was done after the war,” Walter says. “People from Ngerusar, Ngerkedám, and people from a village in Ngerechelong came and did it. That was when all the previous rubak were still living. "They repainted the front end with the history of Airai during World War II. And so they put the Japanese, Europeans, and all the guns, and the history of how the war actually started. The Japanese zero planes flying. That was good. There were a lot of interesting stories. That was very important—a change of history. They saw it and they painted whatever it was that took place. It was the people in the village's version of the war."

|

||

|

|

||

“But then our Historical Preservation office told the rubak that this was not the history of the culture. So it’s painted over, and now it is different. This is back to the normal bai. Before, the local legends were on one side and then they put the war history on the other, so they had both. "I was against it at the time and I still regret it because you know, those guys were some of the very few traditional artists in Palau, and you don’t see any Palauans like those guys in those days. That is when our office had just started, and there was a lot of confusion, and a lot of decisions about what should be saved and what shouldn’t.”

This bai, though unidentified, appears to be the Bairairrai, with end-boards showing images of the war. Belau National Museum photograph. |

|

|

“People came out of the woodwork after the war,” Tina says. “During the War they were a bit too careful on a regular basis. They just harvested whatever they could and then went back to their hiding places. Afterwards they went from their hiding places back to their villages. "And back in their villages, they had to gather from the dust, rebuild their villages. They had to get back in touch with the fishing grounds and their taro patches, places they needed just to survive, because the environment was a mess.”

|

|

|

|

|

With the end of the war came a new group of foreigners to bring change to Palau: the Americans.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Airai Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||