|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

“When the Japanese got here, they owned everything," Roke Wur remarks. "You didn’t even own your house platform. You didn’t even own a small piece of land. The few Japanese that first came to Asor made it their center. There were no Japanese on the other islands. These were mostly business men, and they set up a company here where they exchanged goods for the copra. And they owned all the islands because of the copra. So the copra was considered to be theirs."

|

||

|

|

||

“All of these islands were inhabited, even the small ones, far away from Mogmog and Falalop,” Philip says. “It changed during the Japanese time because they brought the people to the main island so that Japanese could make copra on those small ones. “Most people here now are not from Falalop: some are from L'oosiyep and some are from Sohl’oay, but during Japanese time they put us together on one island so that the other islands are uninhabited and they could plant to make copra there. They planted with coconut trees and they used us to make copra for them.”

|

|

|

“The time of the highest population of Asor,” Mariano reports, “it was not entirely Asor people, but people from the other islands. They are asked to come to Asor to work. This was during the Japanese time. The first copra workers would come and clean, clear the land, pile the copra, and others would be opening the copra and taking out the meat; still others would be drying it. "They even built the warehouses for the dried copra, and when the ship came, people would do the stevedoring, transferring the copra onto the ship. But at that time, we’re talking about highest population, it wasn’t really the real people from Asor."

|

"It was people from the other

islands included. That was a time when one could say, ‘oh, there

are many people on Asor’ because of the other islanders. "But that Japanese company also had food to sell. It probably would have been Japanese rice and all that—canned meat and store items. The local people spent most of their time working the copra. That was the time the copra industry was at it’s highest peak, when the copra industry was top here. |

|

|

|

|

A coconut grove, Falalop.

|

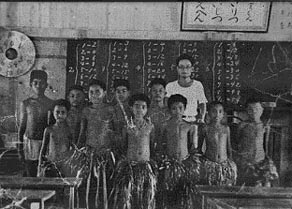

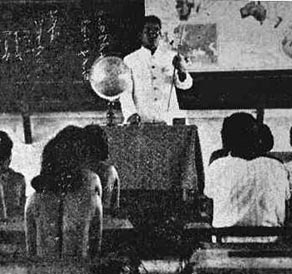

“At that time, the Japanese government had the policy that every young boy should go to school in Yap for five years, to learn Japanese," Manuel says. "Five years. They were rotating people: five years there and then come back to here. And after that, they moved people to Yap, to work like slaves. Barney is one of them."

|

||

|

|

||

“In Yap we had five grades,” Chief Yatch recalls. “And so you could go first, second, third grade, then you could graduate if you wanted to, but if you didn’t want to, then you could continue all the way to grade five. "Everybody went—your whole family went to Yap and stayed there for five years, then came back. We were in Colonia. It was a busy place—they had plenty of stores and workers and so on. “There were separate schools for Japanese children. We didn’t get together. They just separated us from Japanese people, Japanese children."

|

|

|

"They also brought in Okinawans and Koreans. I think Okinowans, they fished. Like long-line and pole fishing. And Koreans, they bring them for laborers. I don’t know if there were separate schools for them. But they didn’t include them with us. Only Yapese and Ulithian. That’s all. "All Outer Island people of Yap, they went to school in Yap during that time. Only boys, not girls. But the Yapese girls used to go to school. For Yap, girls and boys."

|

|

|

|

|

"I was here all the time during the Japanese time," says Flomina Mangelmar of Mogmog. "My parents went with the boys to Yap, to the Japanese schools in Yap. And they lived with them in Yap." “There is a song about when people would be moving from these islands to Yap proper. And we’re not really sure what’s going to happen as they move us from our homes here. It starts with, ‘as we leave, we’re not really sure, on what’s going to happen to us.’ "They’re going to take us to the place of their choice. As we leave there, it’s like they’re going to be isolating us. So we feel sad thinking about our children back home—young children who are scattered around. Some of them are in Sein, a village in Yap; some are in Gargey, another village; some are in Siiutmil, another village; so our children are in these different places. That’s what we mean by scattered around. They cannot live together or stay in one place, so we are wondering what’s happening to them. That’s the translation of one verse." |

|

|

"This song is set either during the War or during the Japanese administration," Mariano notes. "Children are being moved to go to school in Yap, as there were no Japanese schools in these smaller islands. For the parents, this song expresses their longing to see their children, to be with them, to know what’s happening to them. This is a verse of what we can term as the ‘Sorrowful Dances,' one of two types of song and dance we have here."

|

||

|

|

||

“My father, he used to be an interpreter," Juanito says. "He was good in Japanese. He and one of the chiefs went to Palau, before the High Court, to defend somebody. I heard they went there and they won the case." "He used to tell me about his father, my grandfather. A Japanese policeman beat my grandfather until he lost maybe two or three of his teeth. Beat him with a bamboo. And also I heard one day some of the students had been beaten up in school because they came late, or they were caught smoking, and they really them with their sandals, which were made of board, or a piece of stick that they take around. "And I heard about forced labor. Over on Anguar, and also in Yap and Fais. Everywhere. They just beat people."

|

|

|

"The Japanese, you had to do what they tell you," Alphonso remarks. "The policeman, if they arrest you, they beat you up to find out what wrong with you. "And not only that, but even walking in the road, we had to bow down to Japanese people while they salute. That’s the different thing, but if they see you do something bad, just they can do whatever they want and beat you up or something like that. "And in school they beat the students. Not like spank or things like that but they used the bow–the stick they use for bow and arrow, they cut that to about arms length. That’s hard, and that’s what they used to hit us. Those were those people who worked under Tojo!"

|

|

|

|

|

“There was a tower that was built much, much, after the early Japanese time,” Roke Wur recalls. “It was built right before the War got to us. Before the tower was built, other Japanese came and they put up their camp there, and those were separate people from these first ones that came here. Those were military people. “At the arrival of these military people, that’s when they stopped making copra here, because the regular ship that came to pick up copra no longer came to this island. Only the ships that brought out supplies for the military. Not very many. When they made camp here, they started up with observing the weather. They had weather observers with them—not too many, only a few people—but they were military people.”

|

||

|

|

||

The arrival of Japanese military on Ulithi marks the beginning of the Second World War here. To hear about that, we turn to the Memories chapter.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ulithi Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |