|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

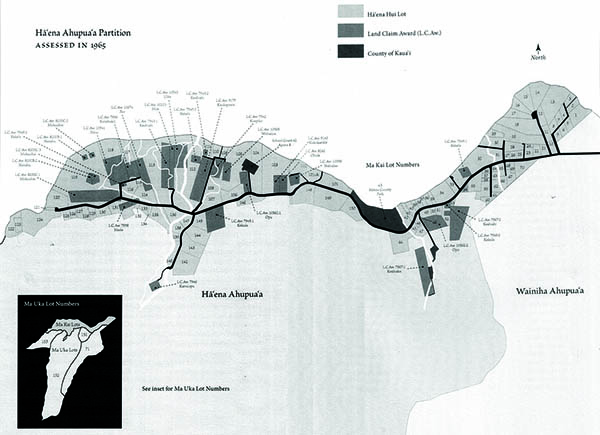

Over time, shares in the Hui Kū‘ai ‘Āina were sold, transferred, and/or auctioned off away from the original members and their families, and into the hands of newcomers to the islands. How did families lose their shares? Many people who had once lived there had moved away, to other places in the Islands or even to the U.S. Mainland. So, many families drawn into migration to urban centers as a solution to finding employment sold familial lands no longer necessary for their new existance. Carlos explains that the land was easily acquired by outsiders “in part because of members not paying their real property taxes. These newcomers bought up the shares bit by bit, by paying the taxes due and purchasing the title in government auctions. As mentioned above, the people moved away, and since they were not really used to taking care of the business of managing land finances, they did not know that they were going to lose their shares." The taxes at that time were often very low, like fifteen cents in the 1920s. But if you were living elsewhere and were and not paying attention, and did not pay, your shares were eventually auctioned off by the courts. It was easy for someone else to buy them up. In other cases, if the head of the household died, the wife received half the shares, and the heirs split the rest. There might have been inheritance taxes too, that people could not afford to pay, so their shares got sold. “Initially there were 39 members in the Hui, and over the years, for the ones that didn’t sell, the interest stayed in the family. Their 1/39th interest fragmented into smaller and smaller shares with each successding generation. So, as the shares got smaller and smaller for individual people, wealthier families (a number from early missionary and/or early entrepeneurial families) on the island purchased whole shares from certain individuals, maybe who didn't have families, or who wanted to sell. And, so the larger parcels passed on to people better prepared to deal with the new governmental, financial, and real property system. “In Hā‘ena, the ahupua‘a stayed intact for longer than most hui lands, continuing to be held in common by the heirs, agents, and successors of the original hui well into the 1960s. The suit for partition into individually held parcels, finally fragmenting the ahupua‘a, was not initiated until 1955. Two wealthy haole, having purchased shares from family members and heirs of individuals who had been part of the original hui, brought the suit before the courts. This initiation of partition suits dealing with hui lands by wealthy individuals or entities who had purchased shares in hui was a frequent occurrence in the years following the annexation of Hawai‘i as a U.S. territory. “The partition is a legal process by which any owner—and this goes for any size property—any owner can initiate a suit for partition. In other words, ‘I want my share, I don’t want it to be held in common.’ The legal term for the Hui is ‘tenants in common’—undivided interests. Instead of ‘okay, you own this acre and I own that acre.’ That’s divided interests. So undivided means you and I own all of this, but it’s undivided. "Now according to U.S. law, or in this case Hawaiian law—which basically comes from U.S. law—any owner can initiate the suit. They sue everybody else for their share, and it becomes a case. And if you initiate the suit, you have to subsidize or underwrite all of the expenses that are necessary to resolve the whole case—the whole legal process is designed to break up lands held in common, and separate individual interests in kind (each owner gettng some land) or in cash (if the parcel is too small for the number of shareholders) generated by an auction by the court. “Once the partition is completed, then everybody else who is an owner has to re-pay the person that underwrote the suit for their share. If you own one one-thousandth of a share, then you will pay back one one-thousandth of the cost of what is now called a 'quiet title.' “An examination of records documenting conveyances of property on the island of Kaua‘i occurring in the decades following annexation reveals that scions of missionary and early haole entrepreneurial families acquired large amounts of kuleana land (granted to Hawaiian citizens in 1850) as well as shares in hui land. This was due, in large part, to their greater access to resources of cash, and their being better prepared to navigate the new economic system. More often than not, there were water rights attached to these lands that could be sold separately from the land itself. During this time, influential haole, many who had been born and raised in the islands, became officers of the hui governing bodies due to their high political and economic status in island society. This was so in Hā‘ena. “There was nobody in the initial Hui who had the wherewithal to pay for or initiate a suit. But the big land owners from the elites of the Territorial period—the sugar families, the missionary families, the merchant families that arose to power in Hawai‘i—were the ones that were buying whole shares, or even fractions of shares from people who wanted to sell. They had the wherewithal to initiate the suit for partition. Philip Rice—member of the kama‘āina Rice family, from whom Chipper is descended—and this guy named John Gregg Allerton—a wealthy Chicago banker—initiated the suit. It took ten years for them to sort through it all to determine who were the present heirs, who were the present shareholders, and to settle on what the land was worth in money. And then it was divided out among the people according to each individual interest. In most cases, there was enough land to divide up, but but as happens in many of these kinds of cases, there were some shareholders whose shares were determined by the court to be too small to be awarded land, and so were given cash. “I think the Rice’s and Mr. Allerton were typical Euro-Americans: they knew system, and knew very well how the system worked. Such people have a different relationship with what Hawaiians call ‘āina today. The land, no longer the elder sibling Hāloa, it is now real estate, the basis of all wealth John W. Gregg of Monticello, Illinois came to Hā‘ena and was adopted by a man named Robert Allerton. Eventually Gregg changed his name to John Gregg Allerton. He built a house next to Kē‘ē beach. Summer homes became an increasingly prevalent part of present-day land use in Hā‘ena. Old-time residents of Hā‘ena were still using the land for production up until the settlement of the Partition: cattle then was an important industry in the first half of the century, taro was a subsistence staple, and fishing rounded out the sibsistence 'necessaries' for the community. Today, tourism dominates. “A lot of these new people didn’t actually live out at Hā‘ena. Allerton didn’t live out there—he had a place out there that he went to once in a while. They just owned it. But people like the Mahuikis lived out there. They had their cattle and their horses running all over the Hui lands, so it was a good deal for them: they get the use of the land but they don’t own it. “But these other people, they own the land but they’re not there using it. Previous to the Partition, the broader Hui lands were not fenced off. Only the residents' houses were fenced off, to protect the houses and personal gardens. But the majority of the land was held communally. So what these relative newcomers wanted to do was to be able to parcel it off, to fence off individual lands so that they could be used exclusively, either to rent, or for whatever reason. They could then legally say ‘This is mine, and I’m going to exclude all else from it.’” In the early 1950s, John Gregg (Allerton), who by then owned almost 14% in the Hui, and Paul Rice (about 7%), petitioned for partition of the land—to break up the Hui Kū‘ai ‘Āina. Everyone who held shares had to claim them in specific acres of land. It was, in a sense, a new mahele (partitioning), in which the communally-owned whole was to be fragmented into private parcels. The Kuleana lands did not figure in this—they had been separate all along. The procedure of the court was to appoint a "commissioner in partition." A lengthy legal process began, to assess the land and determine values and to what each member was entitled. An aerial survey was done 1952. Preliminary plans for partition were drawn up in 1962, and a final plan 1967. With land values assessed, members drew up a list of preferences for lots. Here is an example of the estimated land values, 1952. Hā‘ena Land Values, 1952

“And then when they had the partition, they determined that the value of the lo‘i lands, and the mountain lands or the kula lands. They fixed a monetary value to different categories of land. And then they decided who got what and how much. “The partition didn’t get completed until 1966. Once it was all partitioned, technically they couldn’t run cattle like they used to. People still let the cattle go into the so-called wild lands. But enforcement guys were sent in, and it stopped. It takes a while for the people to adjust, but the law eventually catches up to you.” “With the completion of the suit for partition, the lands of Hā‘ena were finally entirely privatized. This ahupua‘a, which for close to two thousand years had provided a wealth of resources extending from the mountains out into the sea, cultivated and shared by an entire community, was now fragmented and parceled out. In time, it would become, in a great number of cases, a site for vacation rentals, second homes for wealthy citizens from a far away continent, and residences for those with considerable access to monetary resources. “Few aboriginal people have managed to hold on to their original landholdings in Hā‘ena. These remnants of the original Native population persist in the face of ever climbing real property taxes fueled by speculative development and the current ‘flip that house’ mentality. However, within the few surviving families, the skills of traditional fishermen and farmers, the stories passed down from many generations, and a unique sense of humor and identity rooted and nurtured in the special place that is Hā‘ena continue to be manifested.”

|

|

|

With this new privatization of land, the forces that had elsewhere affected the Hawaiian Islands back in the 1848 Mahele now took root here: land became increasingly concentrated in fewer hands, and many families left the area. This exodus of people became even more pronounced after Hā‘ena was clobbered by two tsunami. |

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

||||

| Copyright 2018 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

||||