|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

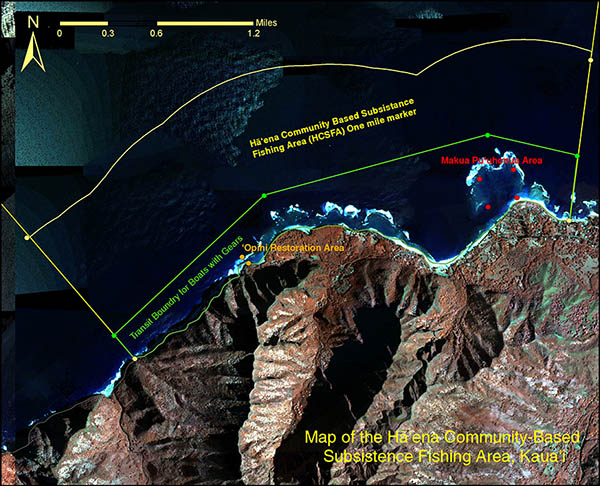

Map of the Hā‘ena Community-Based Subsistence Fishing Area. In 2016, State law 13-60.8 was put into law, establishing the first Community-Based Subsistence Fishing Area (CBSFA) in the state of Hawai‘i. As the community’s proposal states, “The goal of the Hā‘ena Community-Based Subsistence Fishing Area is to sustainably support the consumptive needs of Hā‘ena’s people through culturally rooted, community-based management that recognizes and responds to the connection between land and seaand strives to restore the necessary balance of native species.” What is a CBSFA, and why Hā‘ena? “With the State Park system owning the makai or ocean portion of Limahuli valley,” Carlos explains, “and with Chipper as the head of Limahuli Gardens—which ostensibly owns all of Limahuli valley—what we had hoped to do was to form an organization and weld together all of this land from the mountain top, all the way to the ocean, by linking the State Park to Limahuli—in spirit if in no other way—in order to fashion an ahupua‘a of sorts.” “We didn’t think we [the Hui Maka‘āinana o Makana] were going to do anything with the fisheries at that point,” Makaala says. “It was kind of far back in our minds. But a law was going through the State Legislature to allow for things called community-based subsistence fisheries. That was put together by people from here—representatives from this island. Chipper and Carlos were paying more attention to that than I. “I’m not a fisherwoman, I make entirely too much noise in the water and the fish run away from me like you wouldn’t believe. If you want to see a fish move fast, put me in the water. But I like to eat fish, that was a good motivation. So as that non-profit matured, we were able to get some funding, and that created some of the projects that Limahuli was doing and that the Hui was doing.” “I would like to take credit for it,” Presley remarks, “but it was the dream and the vision of several of the kūpuna from Hā‘ena. My Uncle Charlie would be one of them, and Auntie Kaleihua Ham Young, her son Bobo Ham Young, Auntie Violet, Uncle Tom Hashimoto—there were quite a few kūpuna from that area that had the vision. They felt that it was starting to get over-fished, and they were concerned about the decline in the fish bio-mass in Hā‘ena. They were really concerned, and looking at wanting to pass on to the next generation that same area that fed us so well. We’re just only a small fraction of the people that used to live on that land, and survive on that land, and that land provided for them. “There are many, many reasons for the decline of fish here. I would think like maybe about fifty percent of them we cannot control. But the other fifty percent we do have control over, and that is overfishing. One of the main concerns is people from the outside areas. People will come to Hā‘ena to fish because it is bountiful. I think that’s one of the reasons. Then there is the water quality. "We had 700-something thousand tourists down there a year. Two to three thousand on a daily basis. And they’re doing damage by just taking a shower, washing off their sunscreen. Septic systems are also a cause—more and more cesspools. And global warming. The way we’re going now, it’s just a train wreck. “Anybody live through a hurricane, you would understand the importance. You know people in Honolulu, I grew up over there and very few places that you can go and fish. Yeah, there’s fish, there’s places, but as something to feed us? If something disastrous would ever happen, we’d be up a creek.”

“We eat fish every week,” Kelii says. “When I was living in Hā‘ena, we’re right there, you know what I mean? But how much you need? You take what you need, that’s all. I go fish—we go down on the weekend, we fish—throw net—I have a nice catch. Everybody going to eat them, we get little bit to bring home for the week. We come home, we get fish, we share. So, we eat fish every week.. That was how my father-in-law taught me. “And so looking at that, it kind of put me in a position where I said, ‘You know what, we need to go take care of this—we need somebody for take care of fishing rules. We got to watch our place, take care of the resources, you know.’ Because it’s only easy to go catch the fish, but the work behind that—to keep the fish—who will do that? So I took the step. I don’t mind being looked at as maybe the bad guy that will tell you guys, ‘No touch the fish—nobody go catch this fish this month.’ But hopefully they can catch on why, their thinking: if the fish is spawning, no more catch them. Because that’s how it was when those days: if fish got eggs, why you going to catch them?” “‘Opihi season is closed for two years. People were just raiding down Kē‘ē. You know, how much you can eat? ‘Yeah, I can eat half a dozen!’ That’s why I say, what size you going to pick? Are you going to pick the big ones? Or are you going to pick the quarter-size one, or are you going to pick the nickel-size one? You pick the quarter size one because the smaller one is still growing. The big one, don’t pick the big one—that’s the one that lays the egg. So plenty guys don’t know, they go automatic ‘The big one! Pick the big one!’ That’s the wrong one you guys picking. So this is all education stuff that we need to teach. It’s getting out there. The younger ones don’t know that kind of stuff. Its automatic they figure the pick the big one, you know.” “The uhu is a fish that our divers love to catch,” Makaala adds, “they love to show off the fact that they have a blue uhu. And I explained to them that if you caught the blue uhu then they can’t have any babies until one of the red uhu turns into a blue uhu and becomes the male, it just takes time. They know how to do it, it just takes time. It’s all a process.” “It was a long process,” Nalani recalls. We started in 2006 to do all the meetings with the families and all of that. 2008 was the first meeting at the held in Hā‘ena at the Maka’s garden—about the fishing rules. And that’s when it was decided on what the people wanted. It was presented so that everyone in Hā‘ena ahupua‘a say what they wanted as far as traditional fishing. It was only the families that were from that ahupua‘a. It didn’t entail any of the homeowners that came into the community, it was the people of the original families from the ahupua‘a. From the old hui. And that’s when it was presented for everybody to say what they wanted. And that’s how the rules became what they utilized, for the rules: the old traditional ways of fishing. Because that project out there basically is a linkage between kalo and lawai‘a, because it goes together.” “Most of the information came from me,” Uncle Tom admits, “because none of these people are familiar with that. Because I’m a fisherman. I might be stupid or whatever you say, putting out information, but the information that I put out is for my grandchildren, and for the people in this community. Because this is a community organization. And I was born and raised in here. Nobody knows more than what I know. As far as fishing, farming, everything in this area. I did all that. “In 2006 we went to WestPac [The Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council]. And WestPac had fishermen from here down in Saipan and all over the place. Because WestPac is a federal organization that monitors the fish. Big times. We followed that too, that’s how everything started for us. And that’s what put that in my mind to do what we did. Because I looked at that, and it was just what my Dad was trying to tell us, way back. The old people were conservative. Not only because over here we had plenty fish, they would do crazy and sell it and stuff like that—No. They were conservative. Because they learned in the old way: this place got to be sustainable for the people in this area. They were kind of careful on that. That’s why at that time, they didn’t get information from the Hawaiian then, because the Hawaiians always found that the people—the white people—would get the start and go sell it. That was the problem.” DLNR rules for fishing in the Hā‘ena CBSFA “Opposition comes from commercial fisherman,” Presley points out. “I think it’s like a five hundred million dollar business for the State of Hawai‘i, if I’m not mistaken. I think it’s pretty close to half a billion. It’s a huge. They have deep pockets and they’re a very influential lobby group. But they don’t know the history. They need a serious history lesson about the different fishing zones and seasons practices in antiquity.” “I think for the most part, later when you needed to gather in the people in the community to understand,” Nalani says, “because there was a lot of misinformation. There was a lot of confusion, you know. It was thought that nobody could fish out there. And that wasn’t what it was.” “Being involved in Hui, we really wen learn,” Keliii recalls. “Going to workshops, meeting the different people from different islands. Uncle Mac Poepoe taught me plenty too, just by us meeting every time—beautiful man, just like my father-in-law. I’m always there for all these guys. But when you think about that, yeah, you know it makes sense. But some people don’t have the common sense to think about that, you know? Why they come fish Hā‘ena? Because we have fish. And why do we have fish? because we take care of our fishing. So now that everybody see what we’re doing with our fishing boats, hopefully they can pass the word on to their community, where they come from. “I always say, anybody can come fish Hā‘ena but when you guys come fish in Hā‘ena, just got to follow our rules, respect our place. Simple, and then that’s how it was back then—simple. You no go maha‘oi anybody’s place—stay your place, and that’s how we work. I can’t tell you how much times I surf the other side, two times in my whole life! And lucky I never get caught by my friends. They scold me: ‘What you doing over there. Over here no more surf?’ That’s how they thought. The maha‘oi is a big word for us too, you know. You stay your own place, I just what I tried to teach my kids—they know the culture, they know our lifestyle, they know how things are. And that’s so good, that’s in their blood.” Presley explains how fishing is not a right, but a kuleana. “The first thing is we are going to spend at least another year just on education,” Presley affirms. “Just getting all the fishing shops, all the fishing stores, educating everybody—even today now in Hā‘ena community. There are some families that are still not sure what the rules and regulations are. So, we have a lot of outreach and education to do, at least a whole year of education, and from there we can start enforcement. Or start coming down a little harder on people. “I’d like to see it where we wouldn’t have to have much enforcement. It would be on its own, and everybody would be on the honor system. The DOCARE officers said deterrent is a major force. Once the word gets out, ‘Hey, you guys going to be watching, better not do anything stupid down there, we follow the rules, right?’ So ideally that would be the situation in two or three years.” Learn about the Makai Watch program that monitors fishermen. “This is the first time in 120 years where it’s the closest thing to restoring the konohiki rights,” Presley suggest, “where the community is the konohiki. Uncle Tom is probably the closest thing to a living konohiki that I am aware of. When he is gone, what happens? We don’t have the knowledge that he has, and the konohiki was knowledgeable not only in the fishing and the ocean. But he’s knowledgeable in everything, from whatever is happening way up mauka, to the taro patch and everything down the line to the ocean and in the ocean.” Read about the 2004 whale incident in Hanalei Bay.

|

|

|

|

Maintaining traditional uses of the land and sea is just part of replanting Hā‘ena's culture and values back into future generations.

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

||||

| Copyright 2018 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

||||