|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

"Children with Carolinian decorations, UN Day, 1977." Photograph from the TTPI archives.

|

|

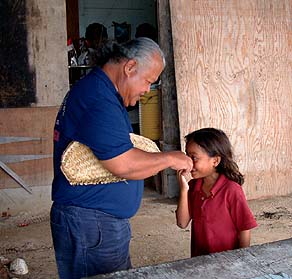

“I enjoy being a Carolinian and Chamorro,” Pete says. “My father is a Chamorro and my mom is Carolinian. But I learned the customs of Carolinian. And I have seen there’s a big difference between Chamorro and Carolinian, in terms of respect in the families: between sisters, cousins and so forth. In the old days, if I’m were sitting down here, my sister couldn’t just walk over to me. As soon as she saw me sitting down, she would just sit down right where she was. She would put herself down. She could not be above my head. That would be disrespectful."

|

||

|

|

||

“We cannot walk straight in if they’re sitting down,” Yoane explains. Cathy adds, “and if they are lying down, we have to get down on the floor.” “The females are not allowed to be above their fathers, their uncles, or particularly their brothers,” Ben elaborates. “They should not stand above them, and so as a form of respect they will bow. They will squat down to the ground and call for the brothers or call for the father, and this man would stand up. That’s when the women will stand up and cross their path. “You know, if I were sitting down and I had a niece crossing a path that is visible to me, she would kneel down and ask my permission to stand up. The only time she could pass my way is when I stand up, and then she can walk. Otherwise she would just continue to stay there until I got up from my sitting position. So they can’t go above our head, so to speak. Those are the rules.”

|

|

|

“If you look back at the history of our culture,” Dave says, “it’s very interesting because if we are relatives and you’re a man and I’m a lady, I have to bow down. If you’re standing, I have to bow down and respect you. Because I’m going to walk towards you, either I sit down where I am, or you go away from the place and then that’s the time I can have the free way for crossing. It is very interesting if you see this area of our culture." “Anywhere," Rosa Castro says, "if my brother is sitting there or my cousin is sitting there, I will crouch very low to show respect for my brother or cousin."

|

|

|

|

“Our brothers respect us and they stand up,” Joaquina says. “When they see us approaching, they have to stand up. It happened in the church, and for me, I am really a church-goer, and I believe that when you’re in the church, everybody is the same. But I realized that my brothers—I don’t actually have real brothers but my cousins, we call each other brother and sister—as soon as they saw me getting up to read, I know they stood up, though they are always at the back. “I said, ‘Why is he standing?’ I completely forgot about it. Because I was going to receive Holy Communion, he stood up. I said, ‘ Why is he standing up?’ Because I was in the church, I thought, ‘Everybody’s the same,’ but they themselves, they really felt that they had to show respect. On both sides: we respect them and they respect us.”

|

||

|

|

||

| “Even now, in front of my parents,” Cathy says, “when my dad and mom stand, my brother’s sitting down, I have to shout to him to please stand up. Because I hate to go down on my knee. With my brother, and male cousins, yes, we still do this.” “It’s another way of showing respect,” Yoane explains, “lf we’re in a group of people, they might not know if it’s your cousin or your brother or what, but when we women do that, they know that 'Oh, these people are related,' or 'Oh, we cannot talk about this person because this…' ”

|

|

|

“I had that experience in Tanapag with my own family here. It happened when I first came here from Namon Weite. When I did that to my male cousins, they went and asked my auntie, “Why’d she do that? You mean we respect her because whenever we saw her sitting down, we have to stand up? Like in the court when the judge walks in?’ They didn’t know; it’s a different understanding. "I talked to my auntie because I cannot just go straight to my cousins and tell them that this is the reason. She’s kind of lost the culture, so I told her that they have to be proud because I respect them, that’s the way I respect my brothers or cousins.”

|

|

|

|

Ben and his daughter wearing mwáár.

|

“Maybe those who are following the Chamorro or American way of life do not do this,” Cathy suggests, “but for us Carolinians, we are still doing it. Even my daugher, she’s only three years old, I always tell her not to walk where my boys are sitting down." “One other rule,” Ben points out, “is that none of my sisters or cousins can touch my head, because it is taboo in our culture. You don’t touch your cousin’s or brother’s head if you are female. I guess the head was very important in those days. “This is where you put the mwáár (commonly called 'mwaarmwaar'), which is to signify where you are in the clanship. Certain colors of the mwáár tell whether you are an important part of the clan or if you are just a clan member. Mwáár is a flower that was woven to be put on the head for certain occasions. We use it for happy occasions such as marriage or sad occasions such as death in the families or in the clans."

|

||

|

|

||

There are also behaviors to show respect for elders: “One time, when I went out fishing, these old people were chasing a big turtle,” Pete says. “There were five of us and we were on another boat. We just went over to them and started to go with them. In the end, I’m the one who caught the turtle. We didn’t give them the turtle. We just put it in our boat. We brought it over to the shore, and we cooked it. And these old men, they went over to my house and told my grandfather this story. “As soon as we had cooked the turtle, I brought it over to the house. My grandfather took that turtle, and he threw that turtle at me. That food was still hot, he just grabbed it and threw it, saying ‘Next time you do this…’ Because I didn’t respect the old people.” “I didn’t repeat that. I knew my grandfather would not accept it. That’s how I learned my lesson well, that you must respect the elders.”

|

|

|

“Mangnginge' is respect for the elders,” Ben says. “It is not a Carolinian practice. Sometimes, although I’m at this age, I would still mangnginge' to another fellow, because it’s my mom’s cousin or first cousin. "The mangnginge' is a Spanish-Chamorro influence, and we carry it on because we believe that respecting your elders is very important. Not necessarily elders, but your immediate relatives. You kiss their hand and they’ll respond back with 'God bless you.' “That’s what Carolinians are all about. It’s that duty to respect your elders."

|

|

|

|

|

Certain gestures indicate respect for the world: “When I’m going fishing," Rosa Castro explains, "there is another custom of ours. I see many of my friends, we go together. But I don’t tell my friends, ‘This is the way I have to do.’ One afternoon I went fishing with my friend, and when lunchtime came, I opened my lunch, she opened her lunch, I picked something from my lunch box and I threw it over, she does it at the same time. I took something and threw it on this side of the boat, she threw some food to her side.

|

||

|

|

||

“And then when we looked at each other, we laughed. I said ‘Eh? I thought it was only me, I’m Carolinian.’ She said ‘no, my mother taught me. I know that custom.’ She offers a little bit of food, throws some, before she puts any in her mouth. "I learned from the old ladies: if I carry food to a place, before we’re going to eat, we have to open the package where you put the food. And if I carry various kinds of food, I take a little of each, and then I move my hand to my other side and I talk to myself. I say, ‘Sorry, because we feel hungry and we really want to eat on your island, here’s your food, too.’ "I believe if you do this, you have no problem—nobody gets sick, nobody has bad luck in the place where we do things like that."

|

|

|

“In 1996 we women dancers went to join the arts festival in Western Samoa. And in 2000, we went to New Caledonia. And I told them our custom for food for the trip, whether on the ocean or in the air. I taught them what they were going to do before they stepped on the island. "So when they invited us to go to Western Samoa, I told my group, ‘Before we go, all of us, we have to buy a little something we carry.’ They said, ‘What for?’ I said, ‘We cannot get down from the plane and step on that island without something to throw down on the ground.’ They said, ‘Why?’ I said, ‘So we will not get sick, or have bad luck,’ like an accident or something. Sick from custom—they say taotaomo’na."

|

“So that is the way. And they say, ‘Okay, ma.’ So when we went to Samoa, I brought some chewing gum, and some tobacco, a cigarette I carried, and when the plane arrived in Samoa, I took a piece of chewing gum and I went down. And I know some guy was looking at me, because he said, ‘Why do you drop your gum down there?’ I said, ‘Because this is my custom. When I go to a new place, I have to offer like tobacco, cigarette, chewing gum or whatever.’ "And they laughed because they understood from their own culture too, the Samoan people. They know what that means. So nobody got sick, nobody had an accident our three weeks there, and we came back.”

|

|

|

|

|

While most of the expressions of respect described here relate to Tanapag's Carolinian heritage, many of the larger village events reflect more of the Chamorro heritage. The first of these is fiesta.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tanapag Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||