|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

The Bairamelengel.

|

|

“The different community associations, like the Young Men’s Associations, were not strengthened during German times,” Tina explains. “Of course that was a different time and era, and the Germans had their own agenda. But right after WWII, organizations of both men and women have resurfaced, and are still very much alive today. Their functions are different or altered, but the capacity is still there. The young men’s association of Melekeok State recently built a bai, and they built the bai in Aimeliik State as well. So that knowledge is being transferred. Right now that’s done by the young men’s associations.”

|

||

|

|

||

“There are new men’s and women’s clubs coming together,” Walter says. “The people, the young kids, they decide that they want a form this and that kind of club. Plus we do have our traditional clubs for men and women. In every village in Palau, they were practiced in the past. There are still states or villages who want to sort of enforce those groups. "The names were invented back during the inception of those traditional governments, and they’ve been carried on. They use those names still. These groups may not be doing exactly what they were doing back in those days, but they are pretty much still sticking to the traditional names. "And when they regroup, then automatically in every village there are people who are supposed to be in this and that position whenever those kind of clubs get together."

|

Traditional Men's Clubs 1. Ngaratelok 2. Ngarachiuod 3. Ngaramekebud 4. Ngaratochedii 5. Ngaratuau 6. Ngaramekekad |

|

Traditional Women's Clubs 1. Ngaraiaml 2. Ngarachochebngii 3. Ngaramesekiu 4. Ngarachesisualik 5. Ngaraseseb 6. Ngaradeel |

“The leaders of those clubs comes from the old village. But all villages sort of have these. The old village clubs, the young men’s clubs, are supposed to be from one end of Airai over to the small villages at the other end. It is still that way now. “These clubs do things for the community, conduct the community services and perform community works: helping doing cleaning or reinforcing docks or the community bai, renovating them or repainted them or whatever is necessary. “However, they don’t really gather like they used to, back in those days, and do what they used to do . Then, they had many people and they could do a whole week’s work in just one day. But not any more. People are so busy working government jobs and others. Only on the weekends do they try to find times to do those community services."

|

| |

|

Traditional bai as shown on Kramer's (1919) map. |

||

|

|

|

|

“These are like the young men’s bai, for the warriors,” Walter points to the map. “They were sort of protectors of these people over here. G & H were bai which were young men’s clubs. J, is another bai which was at the end of the platform, at the end of the path there. F is another bai for a men’s club, next to the dock. And that one E—that is the Bairamelengel. It is sort of a modern bai, they converted it to a modern style bai."

|

||

|

|

||

“The Bairamelengel is the bai for the entire community,” Johnson says. “See, the Bairairrai is reserved for the chiefs only. This one, though, is for everybody: they can have a big party or a reception or a funeral or bands, or whatever you want to have. You can hold it there. “This was built by my uncle, Ngiraked Roman Tmetuchl, in the 1970's, to replace another one which was here before, done by the previous chiefs. My uncle just kind of followed the same building, but made it bigger.”

|

|

|

Another such community bai is near the road to the airport. “That is the traditional bai location,” Walter says, “but the structure is like a proper modern building, not like the Bairairrai. It is concrete with a tin roof, even though it is in the traditional location. And it serves as a community center, like a gathering place. It is public building now, and everybody can use it. “When the rubak in the village gather, that is the only place for them now, then they use it. But any community group over there uses it for meetings. They don’t treat it like when they come into the Bairairrai. It is just like any community center.”

|

|

|

|

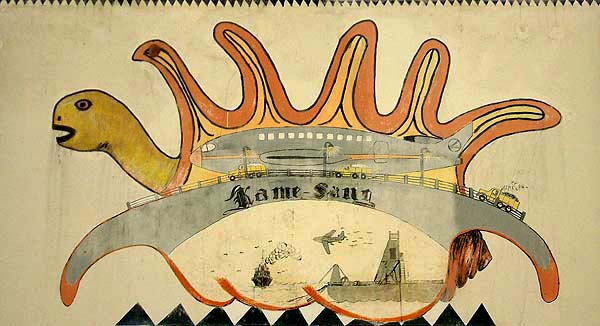

Kamesang. Painting at the Bairamelengel.

|

"There was one huge land turtle in Airai Village," Johnson points to the painting above the door at the Bairamelengel. "Not the sea turtle, but the one that crawls, a huge one, which they all played with. It was roaming the village and the story is that, that was Medechiibelau’s pet, the only one on the entire island. It was a huge one, only in Airai Village. "Our number-two chief’s grandfather, who was born in 1850, said the Airai women took that turtle from Koror, from one of the Western ships. And it was dedicated to Medechiibelau, so it became Medechiibelau’s pet and was highly protected until he died. And the kids used to play with him and ride him around the village. He died in 1944, so Rurecherudel buried him in the yard here near the bai. I think they took the shell to the museum after the war. But he was known as Medechiibelau’s turtle pet."

|

||

|

|

||

"The turtle in that painting is that land turtle, Medechiibelau's pet. And below it is the conch shell. The Japanese word for turtle is kame. And the spider conch shell, the shells which the god of Aimeliik was throwing at Medechiibelau when he stole the school of rabbit fish, is called sang. So that's a play with words there. Kame-sang. Kame is turtle, sang is the shell. "And when you put them together, kamesang is a Palauan phrase for, ‘see, now.’ When you have proven something, you say ‘kamesang.’ Like if you speared a fish or hit a home run. It's a play on words. Kamesang means ‘how wonderful!’ It's a clever way of putting two names together."

|

|

|

"And then Airai State is the site of the airfield, and the bridge to Airai, and so Airai became modern with a causeway to Koror, the ships to Koror and the, before the bridge, that's the bridge to Koror. And the airplane, that's like the modern Airai. "It's no longer isolated. We have a bridge to Koror, we have airplanes coming to Airai. We have ships coming to Palau. It's a modern Palau. This painting is the artist's depiction of the present situation of Airai, because it used to be isolated."

|

|

|

|

“There is always a feeling when you grow up, that the past was perhaps better than today,” Johnson remarks. “It’s the concept of ‘the good old days.’ Because everybody, no matter how rich or how well off you are, you always have unfulfilled dreams or desires. So you either look to the process of having been better in some areas, or you keep striving to improve your lot. “I grew up in a village in Ngiuál with my grandparents, and I have nostalgic memories of those days when we had no modern facilities or appliances. It was firewood, and to make a fire we would use flint stone and coconut husk. You have to put large logs in the fireplace so there is always an ember, so you can always make a fire later. It was fun. It was cozy and warm to live together under those circumstances; it makes you help each other. “Nowadays life is more convenient: you can buy ice cream and you can buy meats, chicken, eggs from the States. You have electric lights and everything. That is okay.”

|

||

|

|

||

| “Yet I think the young people, if they to go to college and read the books, they will eventually realize that we are a unique people, and if we try to emulate our Western or international models, we will fail, because we are not like them, we are unique. So in order for us to be successful and to be happy and to be proud, we must preserve our cultural heritage. And I think they will come to that realization no matter what. It is up to the chiefs to conduct their affairs in a way that will create a cultural environment for these people to return to see, then perpetuate. Those are my thoughts.”

Reconnecting with culture and the environment through education and other means is discussed on the next page, replanting.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Airai Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||