|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| “When it rains in the mountains, water gets collected in the valleys," Ben describes, "and then the force of water pushes out, going out down the valley, a small stream, and pushes itself out to the bay. Water with great force comes out here to the bay, and the erosion is tremendous. As you can see, the water is always red. And that is because of the rain coming from the mountains, coming down constantly. "And what do we get out of that? Some bad, some good. The good thing about it is that it clears all the debris coming from all sides of the mountains, and you know many plants come out here through the bay and they grow alongside, and it purifies the mountains, the valleys, the streams. All the debris comes out here, and as the debris comes out here, you know what fish eat? As the mud settles down on the bottom, fish eat those algae. Like the mackerel, we catch mackerel here during the mackerel run -- in Chamorro, finalågon atulai. Nature has its way of providing."

|

||

|

|

||

|

"The river has always been respected," Joe explains, for that’s where the spirits dwell. We were cautioned and taught not to destroy anything around the river area, or any water area. Normally we’re taught not to make any noise around that area, or there will be warnings from the spirits that you have done that. "And such warnings are bruises on your bodies, on places where you don’t know where it came from. These are ancestral spirits, not like the ancient times, where you have spirits of the moon and spirits of the stars, and all of that. The Spanish came in and all of that had changed, but the respect for the water remains, because of the resource that it brings us."

|

| "Water usage was important for agriculture, for living" Joe adds, "and so people felt the water did not belong to any one particular person, it belonged to the community. Dumping things in the water, that is disrespectful, that would make the elders cry bloody murder if you were to do that. Or if you were to destroy anything within the water." "Unfortunately it’s sad to look now, how we have developments that come in and destroy water, the streams, and make a lot of changes to the geography and topography of the land in the name of development. "

|

|

|

|

"The Inarajan river drains Atate, the interior portion of Inarajan," Rufo states. "The Inarajan river goes up into the hills behind Inarajan. You have the mountain range that runs down the middle of Southern Guam. So the Inarajan river drains a fairly large extent of the municipality of Inarajan. All that Atate area, the tributaries in that area drain into the Inarajan River. "Then on the other side you have the drainage that goes into the Talafofo River. The Talafofo River is the largest river system, and it also has the largest drainage area on Guam. But the Inarajan River also drains a substantial portion of the Southern Guam area. "Right behind Inarajan middle school is a stream, and this stream drains into the Inarajan River. Inarajan used to get their water here. Not any more. Because now they’re getting it from the Ugum River, which is part of the Talofofo River system. The Ugum is a tributary of the Talofofo River. The Ugum River dam—it’s now dammed and piped, and they have developed it. There are tanks and pumps, which get the water."

|

| |

|

|

Streams of Inarajan and their names.

|

|

"We used to have water tanks on the houses. I still collect rainwater. I like to drink coffee made out of rainwater. When I was living in Saipan, Saipan had water problems, and I had a catchment system which we used for drinking, for bathing, cooking. And we only used the domestic water supply for washing dishes, laundry and washing cars. "But we’ve become so dependent on big infrastructure. Rather than be self reliant, people will just rely on the government. They’ll say, ‘Why should I build one, when I can just tap into the system?’ Like sewers, too. We can alleviate a lot of the sewer problems. We have systems that are available that are cheap, for treating your own waste and converting your waste into fertilizer, also for irrigation purposes."

|

||

|

|

||

|

“At the ranch," Therese recounts, "I’d take the kids away so they wouldn’t get underfoot, or trample on the small plants while the adults are watering or spraying. The adults would get upset because the kids would not watch where they’re going. So to keep them busy, we walk into the river, they call it suduk kapitan, in English it’s Captain River. We’d swim, and, oh, the fresh water! "There’s a little waterfall, a one-yard waterfall, and we’d sit in it and let the water run all over us. It’s a tiny waterfall, but the smaller kids enjoy it a lot. And then there are these natural holes that are big and deep enough that each kid can have their own little pool and they just sit in it and stay cool."

|

|

|

|

“When it’s hot and dry, that’s when the water is cleaner. But when it’s been raining, you have all this silt and mud going down, so a lot of times we’d wait until it’s hot and dry, because that’s when the water is nice and clear. “If we’re not planting, we’d just take some food in and congregate next to the river, and eat and laugh and tell jokes. Sometimes play cards. The river has water in it year round, because it’s coming from the mountains. It’s a natural spring river. "There’s another little river there where we used to catch tilapia, We just used a line, and we’d take a little snail and just use the tail end of it, and put it on a hook and put the line in the river. And it’s exciting."

|

|

|

|

|

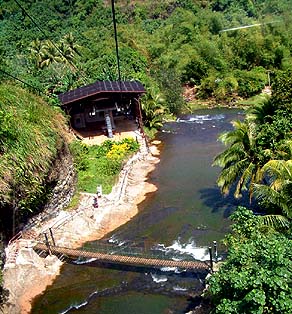

Falls and stream support this ravine ecosystem. |

|

“At the ranch, my father would weave a shrimp trap," Tan Floren recalls, "so when there’s shrimp, my father told me to go and we pulled the shrimp. I got shrimp from the ranch, way out, from the stream. We did it at night and in the following morning. Early in the morning we’d pick up the shrimp and then my mom would sell them, so I had to walk all around by myself.

|

||

|

|

||

|

"And there’s a family down there by the beach, they had a lot of sweet potatoes. In our ranch, we cannot plant that, because there’s no sand there. They need sand because it’s not hard to plant that. So I walk by myself there, and I’d sell shrimp for sweet potatoes. “I’m the oldest in the family, so I would have to go. My brothers were small. That’s what we were eating. Even in here, even milk, you know, we exchanged the milk for anything they had. We had our own cows, my father raised cows, and even carabao. "I had to go around like this with the bottle, I go around selling milk, and we make a little money with that, to get our things that we don’t have. It helps."

|

|

|

|

“Some people, they burned the coconut. But my father, we just grated it, and put it in a small, like a coconut husk, see there’s a hole there. So my father would put it in there, we’d tied it around, and put it down in the river. We’d put it in the evening, then early in the morning you go and you could hear the shrimp splashing at the trap. And you put it down again in the evening, and you could pull out enough for dinner. “Either you boil it, or you cook it with coconut milk and put in vegetables. Oh, it’s good. Delicious. Or make it kelaguen. Now, you can just go to the supermarket, and get the box. "Nowadays, I think none of them are catching the fish. In those days, the river was clean, but nowadays you have to be careful. You know, way up in the mountain, some of them might put poison, so we’re afraid.”

|

|

|

|

The close relationship of water to food leads us to look at planting in Inarajan.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Inarajan Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||