|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Kaniakapupu is the only remaining structure associated with Kamehameha III," says Mel. "Here he was able to think with those who surrounded him, away from the pressures of the foreigners. It was a cool place, and they could take off their western clothes, sit down and discuss the government." The ruins of Kaniakapupu lie in Luakaha, the forested upper portion of Nu‘uanu. It served as the summer retreat of Kamehameha III. Kani-a-ka-pupu ("the singing of the land shell") is considered by some to be the most important site in all Nu‘uanu.

|

||

|

|

||

|

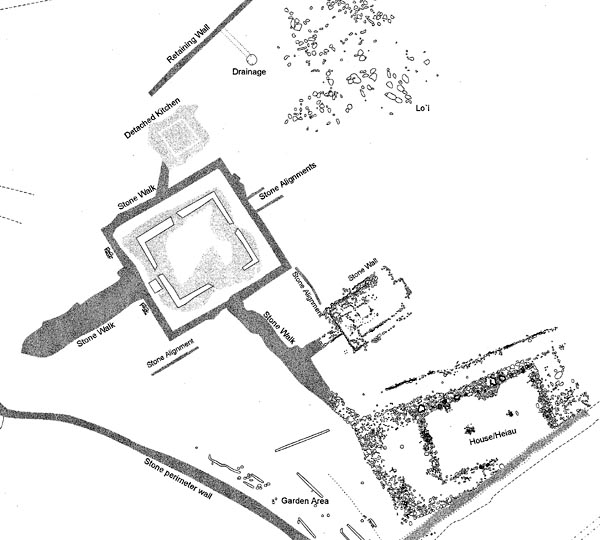

As the King's home, this land would have been kapu and sacred. And the role of Kamehameha III in contemporary Hawaiian history makes this place all the more important. Here, probably, he met with his chiefs to make the decisions that became the 1848 Mahele — the division of lands that ended the old system and created private property in the Islands. It is said a heiau stood here in the old days. One record states that of the two kinds of heiau, those dedicated to Lono served also as rest stations along the highway.

Looking out the doorway of Kaniakapupu. |

|

|

|

The Heiau o Kaniakapupu ("Temple of the sounding land shells") in particular occupied such a strategic position. Charles Kenn (n.d.) wrote,

He later stated, "Here it was that Pai‘ea himself rested his weary warriors during his conquest of O‘ahu." Pai‘ea is another name for Kamehameha I.

|

|

|

|

|

The nature and extent of this heiau complex is not truly known. Though all of Luakaha -- encompassing the entire top third of Nu‘uanu -- was Crown land belonging to the king, the results of the Mahele would carve it up, and a private property called "Luakaha" would quickly take shape just below Kaniakapupu. This luxurious area has been the home of missionary families since the mid 19th century. How extensiveness of the heiau site, then, is uncertain. Lynette states, "If this is truly a heiau site, it doesn’t stand all by itself. There are pieces connected to it everywhere, and we should look at a larger view."

|

|

|

|

"In the heiau, its usually a very wide area where you'd find a lot of people and activity," Kalani says. "Probably other hales -- structures -- were built that went along with that main heiau, and places where people would carry on certain activities because not everything went on at the heiau itself and not everyone could access that heiau. Only a kahuna of that temple could probably be at the heiau. "So the chief or his family or his entourage, or maka‘ainana if they came, would be located in another area. In every heiau area it’s a much wider expanse than that particular structure."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The house itself was not an imposing affair. Reflecting the traditional style, the building itself comprised one large room. It was not, by Western standards, an impressive structure. A Danish observer, Steen Bille (1863), wrote, "It is rather a large building with a surrounding porch, and does not distinguish itself by any architectural beauty ... but if you pass to the rear of its garden you will see a seething fall cascading down from a height of more than 70 feet." At the time, Kamehameha III was living in Lahaina on Maui. He had not yet moved into ‘Iolani Palace (in perhaps 1845). Yet this residence near Honolulu served as an important cultural interface. As Raphaelson (1925) wrote, "Here it was that Kamehameha IV received his training as a true Hawaiian. For the future king was educated in two ways. First he was trained to be a king in the Western style. And then he was brought up here to the valley to his father's palace and trained as a Hawaiian chief." This cultural dualism is seen in the most noted activity of Kaniakapupu, the hosting of feasts in honor of the La Ho‘iho‘i Ea, or Restoration Day. The fourth anniversary of this day was celebrated in magnificent style at Kaniakapupu in 1847. The scene described portrays an incredible occasion, the largest festival ever held in the islands. The scene was recounted in "Holiday Observances" (Hawaiian Annual, 1930):

|

|

|

|

|

| Hawaiians began to go up the valley in large numbers at early dawn. At 10 o'clock the royal party left the palace for Nu‘uanu valley in the state carriage, followed by the military (both infantry and officers on horseback bearing standards), and one thousand horse-women, five abreast, "wearing palm leaf hats and Spanish ponchos, gay with ribbons and floral wreaths." These were followed by 2,500 horsemen. Men stationed at various locations to count the procession recorded 4,000 horses going up and 4,600 returning--visitors from across the Pali making the difference.

|

||

|

||

|

|

At Kaniakapupu, the Hawaiians were accommodated outdoors in "two long lanais, or open-sided ti-leaf structures, thickly floored with rushes, and numerous booths." The "foreign guests," however, were seated at tables in the cottage, and were served food cooked "in the foreign style." Members of the royal party were seated outside. Before dinner the guests were entertained with some of the ancient games, including spear-throwing, lua (the art of bone breaking), and hakoko (wrestling). The most noted expert performer of the day was John ‘I‘i, who had been a retainer to the Kamehameha family. As Rev. H. H. Parker (1937) described it, "In a suit of dark broadcloth he stood in an open square or field, a brilliant yellow feather cape over his shoulders and in his hand a beautifully polished spear. Alone, erect, nearly six feet in height, bull chested and muscular, he presented a splendid figure. Opposite him on the mauka or inland side, stood a group of expert spear men wearing yellow feather tippets and armed with spears tipped with a kind of soft, bushing material. At the signal the weapons began to fly at the human target. ‘I‘i at first parried with his single lance, but presently, as the shots became faster, seizing a passing spear aimed at him and parried with both weapons until the play ended amid the prolonged cheers of a great crowd ...."

|

Feeding this enormous multitude was no small task. The provisions for the feast are described as 271 hogs, 482 large calabashes of poi, 602 chickens, 3 whole oxen, 2 barrels salt pork, 2 barrels biscuit, 3,125 salt fish, 1,820 fresh fish, 12 barrels lu'au and cabbages, 4 barrels onions, 80 bunches bananas, 55 pineapples, 10 barrels potatoes, 55 ducks, 82 turkeys, 2,245 coconuts, 4,000 heads of taro, 180 squid, oranges, limes, grapes and various fruits. It was estimated that there was enough to feed 12,000 persons, and that 10,000 actually were present. The Hawaiian Annual's (1930) recounting adds, "While the feast was going on, several old women in the immediate neighborhood of where the King sat, kept up a constant chanting of meles in his honor and that of his ancestors, accompanying the chant with gyrations and motions of the arms. And in the evening, after the most of the company had departed, a company of hula girls gave a concert with their attendant drum and calabash beaters."

|

Hula pahu (drum).

|

|

What happened to this site after 1847 is unclear. No records have been found so far. An 1874 map notes the site as an "Old Ruin," which is taken as an indication that it had, by that point, been neglected for some time. Others feel that this site has been intentionally neglected down to today. Could it have become nothing more than an "old ruin" so quickly? As we will see in the Visitors chapter, a chunk of the the Luakaha area just below Kaniakapupu moved from being Crown Land to private property. In the Onwards chapter, we will see that there is a strong movement today to restore this site and call attention to its importance in the history of Hawai‘i.

|

|

|

| This and other sites in Nu‘uanu remain the focus of Hawaiian tradition and identity. But tradition also rests in uses and understandings of the environment. Our attention now turns to the Sea.

|

||

|

|

||

| Language | Sources & Links |

| |

|

|

|

| Nu‘uanu Home | Map Library | Site Map | Hawaiian Islands Home | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||