|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

“The Germans came in 1899 and stayed until 1914,” Noel explains. “After the Spanish-American War and the Spanish lost, they gave Guam to the U.S. and they sold the rest of the Marianas to the Germans.”

|

||

|

|

||

“The transition from Spanish to German rule was very peaceful,” Scott elaborates. “When the Spanish sold the islands, the Germans came out and they gave each other salutes. It was very chivalrous. The local people were happy to see the Germans, because for a brief period of time between when the US acquired Guam and the time that the Germans acquired the Northern Marianas, there was a period of perhaps several months when the Spanish moved their headquarters to Saipan. "And along with that came a garrison of mercenary troops from the Philippines. The first governor here was what they would call a ‘Filipino’ in those days, but that meant he was a Spaniard who was born in the Philippines."

|

|

|

"Eugenio Blanco had been the first governor of the Northern Marianas, and he had his garrison of Pampangan troops, and apparently they basically did what they wanted to do during that time period they were here. So when the Germans came in and the Pampangans were leaving, the people here were so happy." "There were at the most only seven or eight Germans on the island. The Germans organized things and they had rules and they did public works projects. And so everybody was pretty much comfortable with the Germans. They thought they were cultured, and they treated the people well and everything was nice and laid back."

|

|

|

|

|

"Georg Fritz, the German administrator here, was a very interesting character. He championed the Chamorro cause. He felt that Chamorros were his kind of people. He didn’t have the same feelings for the Carolinians because their lifestyle was almost in total opposition to what he believed in, but Chamorros, they had nuclear families, they understood the concept of private ownership, they aspired to building nice houses and accumulating wealth and that sort of thing.

|

||

|

|

||

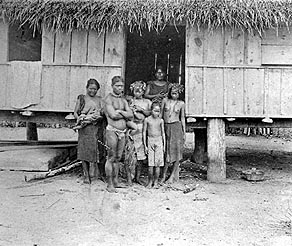

"And the Carolinians were totally communal: 'We don’t care what our houses look like, we don’t want to become rich, we don’t want to own land because we have clan lands,' and that sort of thing. So everything that Fritz believed in was much, much more represented by Chamorros than by Carolinians." "Fritz was responsible for kind of integrating the two groups because prior to his time and even after his time, they were like separate groups. There was some friendship and there were no problems, but they were distinct. There was almost no inter-marriage: the Chamorros lived in their place and had their customs, the Carolinians lived in their place and had their customs."

|

|

|

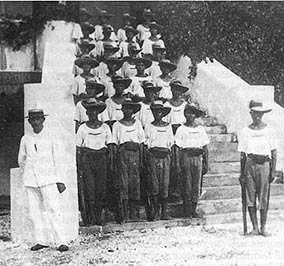

"Fritz was trying to get the Carolinians to adopt Chamorro customs. One of the ways he did it was he created a police force, and he had both Carolinians and Chamorros on the police force. He was teaching them to be punctual and all the things that he thought were important values. "I think he really laid the ground work for what’s kind of become in more recent years the 'Chamo-linian' concept, which never existed before. Maybe it’s a stretch to think he had something to do with it, but I think he probably did."

|

|

|

|

|

"The land tenure was instituted back when the Germans were here," Juan says. "When the Germans came in 1899, they used it for copra because copra was their interest. They didn’t care about the land, they said, ‘All right, if you can plant coconut from here just as far as you can see, that property belongs to you. Just plant and give me copra and we’re fine’."

|

||

|

|

||

“The Germans had various schemes to encourage the planting of coconuts," Scott adds, "and they did tie that in with being able to hold onto large parcels of land. Fritz especially wanted to see land being utilized. And he felt that if you weren’t using it, then you didn’t need it, and it would be taken. "So they did break up some of these large Spanish land grants that had been given out in the 19th century. Jose de la Cruz had 350 hectares somewhere and had like five cattle on them.”

|

|

|

"Fritz was the one that registered local lands, locally private-owned lands. The German administration didn’t want to see him do that at all. They wanted him to record public lands, but he made sure that everybody had their title and this is your property and here’s your deed, and he gave homesteads. "One of the interesting things, he gave homesteads to Carolinians so some of the fee simple privately owned lands that Carolinians have that are not clan lands were derived from Fritz’s homesteading policy. 'Once you get your land, I want you to build a house, I want you to live there with your wife and kids, your nuclear family, be productive. Plant coconuts'."

|

"My grandfather worked for Georg Fritz during the German administration," Noel recounts, "and he told me that everyday he had to go down there and attend to Fritz: cook for him, do the gardening, take care of things around the house. And Fritz always used him when he was going out. Whenever Fritz said that he wanted to eat fish, he had to go look for fish to buy. He was a messenger, an errand boy. "And he started to learn the German language. He went to school, but yet, working there was another addition to his education. On Sundays he and his mom and his father and brothers would always go to mass, and they all wore white straw hats. And always after that, they watched cock fights. That was a pastime already.”

|

|

|

|

|

"Fritz did a lot of good things and some things that he shouldn’t have done," Scott states. "Another thing that Fritz did that I guess was offensive would have been his forced resettlement of Carolinians from other islands. He had the idea that he wanted to increase the population here, to make Saipan more productive, and he needed bodies to do it. "And so he would go after a typhoon would hit, maybe down in the outer islands in Yap. He would arrange to get down there and then encourage the chief to resettle people up here. And he was actually rebuked for that, towards the end, and he left Saipan. "He ended up leaving colonial service around 1910 under unusual circumstances. We’re not really sure if he took affront to having somebody criticize one of his policies."

|

||

|

|

||

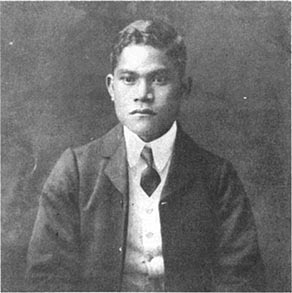

"The Germans provided opportunities for very enterprising people. Two Chamorros were sent to Germany, Josef Ada and his brother, and they lived with Gaylord Fritz’ parents. There they learned different skills: photography and pastry baking and soap making, and different kinds of things. Josef Ada learned photography when he was in Germany. "There was a couple of other people that were sent to China by the Germans. They had their colony there, in what used to be called Tsingtao, and they sent Gregorio Sablan and they sent a guy that learned shoemaking and there were a handful of people."

|

|

|

"Under the German administration, if you wanted to do it, you could probably get sponsored somewhere; if you had the ambition and the interest, you probably had the opportunity. "So the German period was looked back on as kind of a Golden Era. It was when the resources were still intact, the Germans were here but they were in a tiny minority, they had no real impact, the local people were pretty much free to do what they wanted to do within the basic parameters of German edicts, and things but they weren’t oppressive, really."

|

|

|

|

|

“Japanese pulled in one day at the outbreak of World War I. They were ostensibly allies of Great Britain. They kind of had their eyes on this place for a while and they came in with a naval detachment. About 500 armed marines pulled up on the beach. My daughter’s great, great, great grandfather was a sergeant in the police force and he wanted to lead opposition. He wanted to get the police force together and meet the Japanese at the beach and he was dissuaded in that, and so the takeover was quite peaceful. The Japanese were here. "The Japanese weren’t sure whether they were going to be able to keep this place; they weren’t sure what was going to happen with the League of Nations, and so they had a military government that went from 1914 to about 1921 and during that time, it was kind of status quo. They didn’t do a whole lot, although they started to get some of their business interests out here. There were a couple of failed attempts at establishing sugar cane agriculture.”

|

||

|

|

||

“But once they got the green light from the League of Nations, they knew they were going to be allowed to keep the area. That’s the time when they really started getting active, and the Northern Marianas, I think, was the first place where they really started doing things. “This fellow Matsue came out, and he was an experienced businessman who had dealt with sugar cane perhaps in Taiwan. He had a Master’s degree from Louisiana State University, in tropical agriculture or something, and he graduated in the class of 1905. I think he made his money in Taiwan, and then he came out here. "There had been a group before him that just fallen on its face; in fact they stranded around 1500 workers here. But Matsue took the time. He crawled all over the island, he figured out where the good soils were and laid things out, and he actually got things organized here."

|

|

|

“So sugar became the major

cash crop here and pretty much every place that you could grow

sugar cane was cleared and planted, island wide. "They put in their little narrow-gauge railroads and they had their sugar-refining mill, and they built the company town of Chalan Kanoa. There was never a village there—in the German times, it was a copra plantation. But that’s where the mill workers lived. And the Japanese were really industrious, and subsidized heavily, including by their military."

|

|

|

|

| The arrival and colonization by the Japanese would dramatically change the islands, including their population. In the next page, we look at the people of Tanapag during the colonial period.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tanapag Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||