|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| |

|

|

|

“Up until kind of late 1943, the Marianas was always sort of a backwater in the War, “ Scott says. “But then the capture of the Marshall Islands sort of shook up the Japanese, so they were rushing building materials and reinforcements into here. But unfortunately, or I guess it would be fortunately for the U.S., they started at a time when the U.S. submarine presence here was really heavy, and the Japanese were having a really hard time getting the materials in. They were losing a lot of ships, and so they never finished their fortifications."

|

||

|

|

||

“When they finally started trying to reinforce the islands, they were having a really hard time at it because the ships were getting torpedoed, and they’d pick up survivors who’d be without weapons, and a lot of them would be terribly burned and wounded. "The Japanese Navy ships were dropping these groups off here, and then they’d have these straggler units that would come in that weren’t even supposed to be here but they got torpedoed some place, and this was the closest place to drop them off. So there weren’t a whole lot of really high quality combat troops that came to Saipan. "

|

|

|

“The Japanese were stretched at the time, and just didn’t have a whole lot of manpower left. Yet the Japanese were able to get troops in, and they put up what fortifications they could, so they made a pretty hot reception. They did have some heavy guns in place that did a lot of damage—big howitzers that had the beaches zeroed in—so there were a lot of casualties during the initial invasion when the U.S. Marines were hitting the beaches. "After that, there was a lot of bloody fighting, but the U.S. had numerical superiority and air superiority, and the ships were offshore with supplies, so it was pretty much a lost cause for the Japanese."

|

|

|

|

The inner chamber of the cave above Tanapag.

|

“The war was imminent and approaching,” Rosa Castro recalls. “They moved the people, they went up to the dry creek, Saddok Dogas. They moved people away from the village: each and every one to their farm. I didn’t have a farm, but we went and stayed with the Camacho family in San Roque, because he’s my brother-in-law. We stayed one week in the cave north of the Plumeria Hotel. One evening, a big bomb fell next to the cave, and all the dirt came into the cave. “Of course it was very scary, because it buried us, and we had to run out of the cave. We ran up the road to the San Roque church, at 11:00 at night. When we left that cave we headed toward San Roque church, going up to what is the Camp Pacific area now, but we ended up staying two weeks in between rocks. And then we saw the Americans approaching."

|

||

|

|

||

“We were scared because we didn’t know what to expect. But the Americans did not hurt us. The Japanese up above us in the cave would throw dynamite in the cave. My cousin died because the Japanese threw dynamite in the cave. “Six American soldiers, when they heard the Japanese throw dynamite into our cave, they ran toward us, and we were running also out of the cave. They took us. Because we were so scared when the Americans took us, we forgot my mom. And we forgot Filipe, my brother, and they forgot Filipe’s mom. And we forgot Jean Repeki’s mom. They were all still in the cave, half buried.

|

|

|

“I have a brother-in-law who understood a little bit of American language. The Americans said ‘Do you have any more people in the cave?’ Then they saw that three old ladies were not there. And the six American soldiers and the four brothers-in-law went down again to the cave and brought the three ladies back. “What did we eat while we were in the cave? Aye, aye, aye! We don’t eat. We just ate sugar cane. Everybody got sugar cane, a sugar cane bundle about 12 inches in diameter. They peeled it and that’s what we ate. Everybody would drink. We would eat sugar cane like water. You drink water like you eat food, because sugar cane is the thing all of Saipan used to drink water from and eat. We later got rations during the military time—‘46, ‘47, ‘48 . But during the Japanese time, no, nothing. You work, you eat.”

|

| |

|

|

“I was here on Saipan building the airport in 1941 when the first American airplanes came and bombed the airport at As Lito Field," Jesus says. "I don’t know whether it was scary for me, because I really didn’t know war. When the invasion arrived on Saipan, then we were shipped out to Pagan. In 1942, the Americans had already landed on Saipan, and that’s when they started bombing on Pagan. “I had been in Pagan doing forced labor with the Japanese to make an airfield there, and then we were shipped out of Pagan to come to Saipan and do the same thing: open up an airfield for the Japanese planes. My father owed some money to the Japanese, and that’s the reason why we had to go to Pagan—to pay for his debt."

|

||

|

|

||

“We worked up there with our hands, with pick and shovel. We used dynamite, but no heavy equipment: no bulldozer, no backhoe, no nothing; only picks and shovels. And we built what must be huge runways. It was very hard work: one person would have his pick and shovel, and there’s this cart that runs on the train track that you had to fill up. One person would fill that while you’re working every day. “It’s so hard and difficult. The Japanese would feed us at 4:00 in the morning, one small bowl of rice and small bowl of soup, and we were not allowed to bring our own food or we would get the stick on the back. Life was hard, because that was the only place they fed us. And if you didn’t work, you didn’t get fed. Well, it wasn’t so much for the food, but it was an obligation that we had to go and work at the airport, or we’d get punished."

|

|

|

“In Pagan we were working on the airfield. Again, it’s all by hand. No equipment whatsoever. While we worked during the day, the Americans would come and bomb and kill Japanese soldiers. And when this afternoon bombing became more often on Pagan, we quit working during the day, and we worked at night. So, when we started working at night and these small planes flew by and saw many lights at night, then they start bombing again, and shooting. So night and day we didn’t work anymore. "There were a lot of Japanese soldiers, and I went with them to this place called Talague on Pagan, and stayed there until the war was over. When the war ended and the Imperial Japanese surrendered, they dropped leaflets, papers, telling us to take all the war equipment and pile it up in one place."

|

“The Japanese soldiers, all they wanted to do is cut your head off. Did you know that when we were in Pagan the Japanese were really going to kill all the Chamorros? They suspected all Chamorros to be American spies. There was a cave in Pagan village, going toward the other side of the ocean. They put gasoline inside the cave, and they were going to bring us in the cave and ignite the gasoline. We were to be killed in that fashion. “But luckily the Americans came and bombed Pagan, and changed the Japanese plan. It’s some act of luck that the Americans invaded Pagan, because the Japanese plan was to kill all the Chamorros in that cave. There were about 200 Chamorros up there, but a lot more Japanese soldiers. “You could not act like a man over there, because they’d show you their sword. They’d cut your head off. We were lucky, because a couple of Chamorros had been tied up already to have their heads chopped off. The Chamorros would be asked by the Japanese to dig their own graves, and then their hands were tied. Then the invasion came and they were released—in the nick of time.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

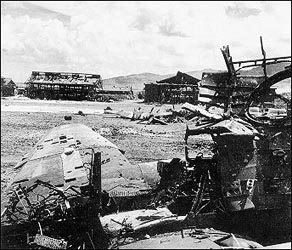

“Tanapag village was right in the middle of the gyoksai attack," Scott points out, "the Japanese ‘banzai charge,’ as the Americans called it. That’s where the two army battalions were overrun by the Japanese, kind of the last organized attack of the battle. It was quite a bloody battle there. I think the Japanese lost about 3500 men. The U.S. lost several hundred, and that area was all bombed and shelled and dug out and people were buried."

|

||

|

|

||

“At the beach in Tanapag where I lived, when I was first there, anytime that there was a storm, there would be skeletal parts washing out of the beach. Japanese bone collectors used to come over once or twice a year—now they come much less frequently—and they excavated right between my house and the guy that lived just on on the other side of me, and took out maybe 50 or 60 skeletons. That whole area is just one big massive graveyard. “The problem with that area is you’ve got a mixture of the World War II stuff and then you’ve got ancient stuff because that was obviously a village area in ancient times. So sometimes you’ve got a Japanese World War II casualty that’s buried exactly next to a 1500 year old indigenous latte-phase burial.”

|

|

|

“As it was, the Japanese got blasted. Pretty much everything on the island got blasted. There were many civilian casualties: both Japanese nationals and locals got caught in the cross fire, and there were a lot of Japanese nationals that committed suicide. Some of them didn’t want to commit suicide but were forced to, but others did it freely. “It would be hard to think what this place would have been like if the Americans hadn't come when they did. It would have been another Iwo Jima if the Japanese had had another year to reinforce positions and to get some first-rate combat troops in here. It would have been a totally different battle.”

|

|

|

|

|

The War was just the beginning of major changes to Saipan. In the wake of the War, all residents of the Northern Mariana Islands were moved to internment camps. Local elders still remember life in the camps.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tanapag Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||